Alsea township

A little over a year ago, on September 11, 1978, in southern Oregon, three men barricaded a road with cars and shotguns. They were waiting for 30-year-old Michael Howard, a ranger for the Forest Service, who was on his way to take weather readings in the area. If his measurements of the wind velocity and humidity were within the legal limits, a 590-acre area would be sprayed with the herbicide 2,4,5-T.

As he approached the barricade, one of the men fired a shotgun three times. A local newspaper reported Howard's reaction. His version was dry and unemphatic.

"I got out and talked to them a little bit about the situation and what was going on," Howard said. "They told me there were people in the spraying area who were hunting rabbits, and that they would be there all day.

"So at that time we decided we wouldn't spray that day. I just went back to the office."

The newspaper reported that after a hurried conference in Salem, Forest Department officials called off the spraying of that particular tract, not only for the rest of the day but for the rest of the year.

And District Forester Steven Jacky said the helicopter firm contracted to do the spraying "didn't want to go back out there with the ship and get it shot out of the air."

The message was received, loud and clear.

But it wasn't until 1970 that the U.S. government first limited the use of 2,4,5-T on the basis of animal tests. Its use was stopped where there was a high risk of pregnant women being exposed.

Then, early in 1978, a federal government body, the Environmental Protection Agency, called for a review of the uses of the herbicide because of a series of significant animal tests. The EPA said its calculations showed that people applying the chemicals, or exposed to the spray, may not be safe.

The tests show that exposure to TCDD to laboratory animals of several different strains and species gives repeated and regular symptoms of damage. They include death of the foetus, reduced foetal size, skeletal deformities, intestinal bleeding and abnormal kidneys, and a reduction in the chances of survival of the offspring. The EPA also cited studies that show the chemicals have caused leukemia or lung, liver or other tumors among mice and rats.

The Carcinogen Assessment Group has added its voice, saying there is substantial evidence that the dioxyn TCDD is likely to cause cancer in humans.

Dow Chemical Company, which manufactures the herbicides, has since tried to suppress the publication of the results of tests carried out in its own laboratories that show damage to animals exposed to TCDD. The tests demonstrate a large number of problems suffered during reproduction, including miscarriages, stillbirths, and ill-health and death among the young that survive. Even at the lowest dosage there were significant increases in the number of stillbirths, and deaths before the young were three weeks old.

Dow Chemical Company claimed that the results of the studies are "trade secrets" or "confidential" and won a court injunction against the EPA's disclosing the data at this time.

But it wasn't the animal research, which the EPA describes as almost unprecedented in its conclusiveness, that finally led to the emergency ban on 2,4,5-T and the related herbicide Silvex. It was the careful and dispassionate gathering of evidence and documentation by one woman - 33-year-old Bonnie Hill, a school teacher at a small country school in the tiny settlement of Alsea in southwest Oregon.

It was her work, carried out for more than two years in her own time and expense, that sparked further investigations by the EPA. What it discovered was sufficient to justify an emergency ban on the herbicides while fullscale hearings took place on whether the ban should become permanent.

Bonnie Hill's work had tipped the balance. It was the first time any substantial link between the use of chemicals herbicides and damage to human health had been established.

Yet her communication is never arid. It is always informed by her deep commitment and lively interest in the subject.

Bonnie and her husband, Tony, were both born into military families and raised as Catholics. Her father was a doctor in the Air Force with the rank of colonel; Tony's father was an Army colonel. They both travelled extensively as children, following their fathers as they were transferred around the world.

They were married in Wisconsin and had the first of their four children there before they moved to Alsea in 1966.

"It was the only place neither of us had lived before," says Bonnie. They wanted to be among the mountains, the rivers and trees, and be near the ocean.

"We know we wanted to live in a rural area as opposed to an urban environment to raise a family," Bonnie says. "It's still my favorite place."

From being a teacher, Tony in the next eight years worked in almost every aspect of the forest industry. He harvested seeds, planted trees, thinned them out, logged the trees, milled them into lumber an organized their shipping and sales. He is also one of the few people in the country who specializes in hand-tying flies for fisherman.

Bonnie had two children before her miscarriage in the spring of 1975. Her doctor had no explanation for it and no one thought of herbicides as a possible cause. No one was aware that they were used that much.

A few months later Bonnie came across an article referring to the studies of Dr James Allen at the University of Wisconsin. His studies indicated that exposure to 2,4,5-T caused adverse effects, including miscarriages, upon the reproductive systems of rhesus monkeys.

She immediately realized the possible connection.

She phoned the Bureau of Land Management, which manages the land all around her, and discovered that Silvex and 2,4,5-T had been sprayed in her area a month before her miscarriage.

She thought that could just be coincidental. Then she started to remember former students of hers from the Alsea school having miscarriages and wondered whether their doctors had any explanations. She was careful not to alarm them nor to suggest that herbicides could be responsible. Eventually she found out about other miscarriages.

"I was not inquiring about spring miscarriages exclusively, but about all miscarriages in the area," says Bonnie. "Every time we heard about a miscarriage it was in the spring. One was in October (autumn) - but that year they sprayed in September, so it seemed to fit into the pattern as well."

She also placed a series of phone calls to the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, in the Alsea area. She wanted to know when and where they had sprayed and what the specific sites were. She made no secret of why she was asking questions and she soon realized that some of the information may not be complete. She thought one representative was very helpful and concerned, but "others demonstrated reluctant, uncooperative attitudes. It took many telephone calls and many personal visits to elicit information," Bonnie says. In fact the EPA is still in the process of collecting details of the sprayings because two of the private companies who did the spraying will not release them.

By the spring of 1978, over two years later, she had tracked down 11 miscarriages experienced by eight women. Eight of the 11 miscarriages had occurred in 1976 and 1977, which she found out were by far the years of heaviest application of herbicides for the area. But she recorded only those miscarriages that had been verified by doctors. Most of the mothers were young women who had been raised in Alsea and whose husbands work in the timber industry.

Nine of the 11 miscarriages had occurred in the first three months of pregnancy, which coincides with the findings in the experimental animal tests.

After she had gathered all the spray data she seemed likely to get, she made up a chart listing the dates of the miscarriages, the dates of the herbicide sprayings for each agency and company, and the amounts and names of the chemicals used by each.

"I then drew up maps of exact spray sites based on the admittedly incomplete data that I had," Bonnie says, "and compared them to the location of each woman's home."

She found that the closest lived no further than two miles away. Because she wasn't given complete data she cannot help wondering if the spray sites could have been even closer.

At this point she decided the miscarriages followed the spraying so closely, and the women lived so close to the spray sites, that the facts were too strong to ignore. So she sent out a letter outlining the results and asking for help to research it further. All eight women signed the letter.

The EPA saw the beginning of some solid research on human exposure and stepped in. An agency team of doctors interviewed each of the women using a detailed 18-page questionnaire.

The results were consistent enough for the EPA to undertake a further study of the hospital records of a 1,600-square-mile area of southwest Oregon, including Alsea, over the previous six-year period. It also chose two control areas, one rural and one urban, both of which had little or no exposure to the herbicide.

The EPA found that, unlike the control areas, the 1,600-square-mile area had a remarkably high miscarriage rate and that the rate rose significantly following spray periods.

The findings were solid enough for the EPA to call an immediate emergency ban on all uses of 2,4,5-T and Silvex, except for areas where human exposure is minimal. An emergency ban is the most drastic legal move the EPA can make. One of the main reasons for this ban was to protect an estimated "4 million people across the nation [who] may be at risk through the use of the herbicide."

The EPA says the Alsea studies, taken with animal tests that show the embryo is particularly susceptible to low dosage levels early in the pregnancy, suggest "a possible relationship between the use of the pesticide and the miscarriages reported." The EPA also thinks that Alsea may not be unique. It says reports of people affected by exposure to herbicides have frequently appeared in medical and scientific journals, and the agency has received many reports itself.

The Dow Chemical Company reacted angrily to the emergency ban. UPI reported Dow Company president David Rooke as saying, "Bad science can't be left unchallenged" and "we can't let fear, distrust or special interest build emotion" which results in questionable decisions.

"This is not a chemical that can be capriciously wiped off the market. If you can take this off the market, what's safe?" Rooke asked.

In the face of the gathering evidence, his question is ominous.

Debbie Morano, 25, had four miscarriages in two years. She was one of the eight women cited in Bonnie Hill's original research. She added her signature to the letter Bonnie Hill wrote that eventually led to the emergency ban on 2,4,5-T and Silvex. The Moranos live 30 miles from the Alsea township in a small valley surrounded by tree-covered hills. There are only three other houses nearby.

The walls of the small two-bedroom home have large religious tapestries and paintings on them. The doormat carries their names - "John and Debbie Welcome You" - as does a wood carving over the kitchen door, a wedding present.

Debbie Morano lost her first baby in May 1975 after 14 weeks of pregnancy. "I thought it was just one of those things," she says. "A lot of women lost their first baby, the doctor said. We believed it, why should it be wrong? We believe things, we're fine."

Debbie is small and slim with large tinted glasses. Her speech has a disjointed quality in it, as if questioning the things around her is a role she can't get used to.

"I didn't even know they were spraying," she says. And she thought, "they obviously wouldn't spray anything that is dangerous to humans. I've become very disillusioned."

By the time she'd had her fourth miscarriage, in February 1977, she knew about the spraying and she knew some people thought that the herbicides could be her problem. Her doctor had still found no explanation for them.

She contacted the EPA, which came a took samples of their elk beef shot locally, and their soil. The beef was found free of dioxyn and a chromosome test of her husband was normal, but she's not so sure about the soil.

"I've got letters that are kinda vague," she says. "They deny it but they keep a way out."

So she hasn't kept a garden since then.

Debbie finally gave birth to a son in June 1978. They called him Matthew. "It means Gift of God. We figgered that's what he was after all this fuss," Debbie says. They're moving to Alsea in November and she's glad to go although she knows the same problem is there, too.

Her stories of what has happened to herself, her neighbors and her friends have the cumulative effect of horror. Friends of her husband, a family of four, were soaked with the spray accidentally while hunting in the woods 11 years ago. The mother had menstrual problems six months after the spraying which have never normalized since. Her son, now 13, had bone cancer. When that was brought under control he developed leukemia. The mother was hospitalised with mental problems.

Debbie talked about the people in her immediate area.

"Two neighbors have had miscarriages since they started spraying with 2,4-D [a substitute for 2,4,5-T], one just across the fence, the other just across the field. Out of these four houses there's been two cases of cancer, three miscarriages, and two babies with a problem of yellow jaundice.

"My husband has migraine headaches, which he's never had before. There's just a lot of things, besides, that matter, like flu symptoms."

Each single thing in itself wouldn't have raised their suspicion. But there are so many things now they've become really suspicious.

She looked around at the view. "Everybody lives here to get away from the smog and pollution. But it just doesn't seem a nice place to live any more." She can't quite handle the contradiction. "It's almost funny if you want to be sadistic."

The most obvious effect is the economic impact on the timber industry. The ban means more work but fewer trees to show for it.

Foresters regard 2,4,5-T as a valuable tool because they say it is a cheap and easy way of reducing the competition of unwanted vegetation with the Douglas fir. They say the herbicide is used a total of only three or four times in the first 15 years of the firs' life. Without the herbicide, control of the surrounding vegetation is much less effective, with the result that fewer trees survive for harvesting.

Douglas Liecz, associate chief of the U.S. Forest Service, was reported as saying the ban could cost the U.S. timber industry 15 million cubic feet of lumber at a cost of $20 million a year.

An Oregon report was much bolder. It predicted a loss in Oregon alone of 936 million board feet, and it estimated that 20,000 jobs in the timber and related industries would be lost.

That report may have been too bold. A private economist, Jan Newton, criticised it in detail for its "carelessness, distortion and error." She says the report came from industry sources who inflated the likely loss of timber.

And the loss of jobs for 20,000 people, Ms Newton points out, applies to some 50 or more years in the future when the timber is actually harvested. She says the figure is "not only scientifically indefensible, but absurd."

The EPA estimates the short-term effects could be about $20 million of the first year for increased costs and yield losses, and nearly $40 million the second year. The EPA says, "While significant, these impacts are rather nominal within the context of the overall forestry industry in the United States."

The timber industry and others who support the use of the herbicides often refer to the events in Seveso, Italy, and defoliation practices in Vietnam, in favor of their case.

On July 10, 1976, a chemical plant in Seveso exploded, resulting in widespread contamination of the surrounding countryside with TCDD. Hundreds of animals died, many residents reported skin disorders, and an area of 110 hectares was evacuated.

Reports made in 1977 claim that the pollution was not as serious as feared, most patients were expected to recover completely, and pregnant women exposed to TCDD contamination at a critical stage of pregnancy "have now had their babies without any higher than average incidence of abnormality."

The EPA disagrees. In its emergency order suspending the use of 2,4,5-T it throws a somewhat different light on the aftermath of the explosion. It criticises deficiencies in the data and how it was treated and interpreted. And it quotes other evidence showing that the congenital malformation rate increased seven-fold in 1976 and the first five months of 1977. The birth rate dropped "sharply" following the explosion, and a local doctor noted a "marked increase" in convulsions among infants.

The defoliation program in Vietnam used Agent Orange, a herbicide mixture contaminated heavily with TCDD. It was aimed at completely destroying the vegetation, and was applied at four times the rate allowed in the United States by large aircraft flying several hundred feet above the ground. The highly poisonous contaminant TCDD was 25 times stronger in Agent Orange than is currently allowed in 2,4,5-T.

The events in Vietnam have made it difficult to assess what the effect of this heavy concentration of poison was on the population of Vietnam. The EPA has some evidence which suggests the defoliant affected children's health. And nearly 500 Vietnam veterans believe their contact with Agent Orange affected them. They are claiming disability benefits for problems ranging from deformed children to nervous disorders.

One of the reasons the dangers from the herbicides didn't receive close attention was the lack of knowledge about how they can spread. There are a number of ways in which the poison can be absorbed - by breathing it, eating it, drinking it, or even getting it on the skin.

At first it was thought that 2,4,5-T was not too dangerous because it soon broke down in the environment. But the contaminant TCDD, says the EPA, "has a much longer persistence in soil and is known to bioaccumulate in fish." One thing that all eight women in Bonnie Hill's research had in common was they all ate fish and game caught locally.

Recent studies have shown that the herbicide spray can drift much further than previously thought. A draft report of the EPA to Congress says the percentage of herbicide drifting more than 1,000 feet from the target area ranges from 10 percent to as much as 90 percent. And it says some of it has been reported as far as 22 miles from the target.

The only drift study made in the hilly forested area of Oregon near Alsea shows, despite optimum conditions and the observance of all restrictions, 70 percent of the herbicide found its way into a nearby stream.

The EPA found TCDD in the sediment of a stream from which one Alsea woman draws the water for her family. The woman has had two miscarriages, and her 4-year-old son, conceived during the spray season, had a history of serious respiratory problems.

Some reports on 2,4,5-T consider what they call "worst case estimates." The 1977 report made by the New Zealand Department of Health put up the example of a woman sprayed with 2,4,5-T so her entire skin surface was covered. The report concluded that the safety factor was still sizable and the intake of 2,4,5-T would be far below the "No effect level" in animal studies.

However, the concept of a "no-effect level" has been discredited. The World Health Organization and the National Research Council of Canada agree that a "no-effect level for man could not be established."

An EPA spokesman in Seattle said that TCDD, the most poisonous chemical made by man, can occur "in such minute levels that we don't have the ability to test and find it."

And speaking of Bonnie Hill's work and the investigations that followed he said, "We may have to, for a while, rely on this kind of information, these kind of probable links."

Scientists cannot study humans in the laboratory or even in the field with the ease and control animal testing. Nevertheless, Bonnie complains, many will not take any notice of people's accounts of how they have been affected because their evidence is "anecdotal" or "circumstantial."

"Somehow, we ordinary folk are left to 'prove' that we have been adversely affected by a foreign element in our environment to which we are exposed without our consent - and whatever 'proof' we have to offer is rarely accepted," Bonnie told the subcommittee.

In the face of the difficulty in obtaining hard data such a rejection can be dangerous.

She asks, "What else is there left, besides people who are able to observe things that are happening around them, and who are able to reason that certain relationships are most certainly possible?"

Northwestern Magazine, Portland, Oregon, 1979

As he approached the barricade, one of the men fired a shotgun three times. A local newspaper reported Howard's reaction. His version was dry and unemphatic.

"I got out and talked to them a little bit about the situation and what was going on," Howard said. "They told me there were people in the spraying area who were hunting rabbits, and that they would be there all day.

"So at that time we decided we wouldn't spray that day. I just went back to the office."

The newspaper reported that after a hurried conference in Salem, Forest Department officials called off the spraying of that particular tract, not only for the rest of the day but for the rest of the year.

And District Forester Steven Jacky said the helicopter firm contracted to do the spraying "didn't want to go back out there with the ship and get it shot out of the air."

The message was received, loud and clear.

* * * * *

The herbicide 2,4,5-T was registered for use in the United States more than 30 years ago. During its manufacture the dioxyn TCDD is formed as a by-product. This dioxyn is known as the most poisonous chemical ever made by man.But it wasn't until 1970 that the U.S. government first limited the use of 2,4,5-T on the basis of animal tests. Its use was stopped where there was a high risk of pregnant women being exposed.

Then, early in 1978, a federal government body, the Environmental Protection Agency, called for a review of the uses of the herbicide because of a series of significant animal tests. The EPA said its calculations showed that people applying the chemicals, or exposed to the spray, may not be safe.

The tests show that exposure to TCDD to laboratory animals of several different strains and species gives repeated and regular symptoms of damage. They include death of the foetus, reduced foetal size, skeletal deformities, intestinal bleeding and abnormal kidneys, and a reduction in the chances of survival of the offspring. The EPA also cited studies that show the chemicals have caused leukemia or lung, liver or other tumors among mice and rats.

The Carcinogen Assessment Group has added its voice, saying there is substantial evidence that the dioxyn TCDD is likely to cause cancer in humans.

Dow Chemical Company, which manufactures the herbicides, has since tried to suppress the publication of the results of tests carried out in its own laboratories that show damage to animals exposed to TCDD. The tests demonstrate a large number of problems suffered during reproduction, including miscarriages, stillbirths, and ill-health and death among the young that survive. Even at the lowest dosage there were significant increases in the number of stillbirths, and deaths before the young were three weeks old.

Dow Chemical Company claimed that the results of the studies are "trade secrets" or "confidential" and won a court injunction against the EPA's disclosing the data at this time.

But it wasn't the animal research, which the EPA describes as almost unprecedented in its conclusiveness, that finally led to the emergency ban on 2,4,5-T and the related herbicide Silvex. It was the careful and dispassionate gathering of evidence and documentation by one woman - 33-year-old Bonnie Hill, a school teacher at a small country school in the tiny settlement of Alsea in southwest Oregon.

It was her work, carried out for more than two years in her own time and expense, that sparked further investigations by the EPA. What it discovered was sufficient to justify an emergency ban on the herbicides while fullscale hearings took place on whether the ban should become permanent.

Bonnie Hill's work had tipped the balance. It was the first time any substantial link between the use of chemicals herbicides and damage to human health had been established.

* * * * *

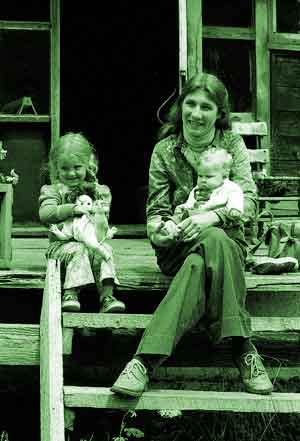

Bonnie Hill is a tall, slim woman with a strong, serious, almost gaunt face. Her voice is soft but clear and articulate. She feels strongly but always speaks objectively, picking carefully the precise fact, the accurate assessment, the proper context. She refuses to be drawn into emotional or personal issues, relying on the events to speak for themselves.Yet her communication is never arid. It is always informed by her deep commitment and lively interest in the subject.

Bonnie and her husband, Tony, were both born into military families and raised as Catholics. Her father was a doctor in the Air Force with the rank of colonel; Tony's father was an Army colonel. They both travelled extensively as children, following their fathers as they were transferred around the world.

They were married in Wisconsin and had the first of their four children there before they moved to Alsea in 1966.

"It was the only place neither of us had lived before," says Bonnie. They wanted to be among the mountains, the rivers and trees, and be near the ocean.

"We know we wanted to live in a rural area as opposed to an urban environment to raise a family," Bonnie says. "It's still my favorite place."

From being a teacher, Tony in the next eight years worked in almost every aspect of the forest industry. He harvested seeds, planted trees, thinned them out, logged the trees, milled them into lumber an organized their shipping and sales. He is also one of the few people in the country who specializes in hand-tying flies for fisherman.

Bonnie had two children before her miscarriage in the spring of 1975. Her doctor had no explanation for it and no one thought of herbicides as a possible cause. No one was aware that they were used that much.

A few months later Bonnie came across an article referring to the studies of Dr James Allen at the University of Wisconsin. His studies indicated that exposure to 2,4,5-T caused adverse effects, including miscarriages, upon the reproductive systems of rhesus monkeys.

She immediately realized the possible connection.

She phoned the Bureau of Land Management, which manages the land all around her, and discovered that Silvex and 2,4,5-T had been sprayed in her area a month before her miscarriage.

She thought that could just be coincidental. Then she started to remember former students of hers from the Alsea school having miscarriages and wondered whether their doctors had any explanations. She was careful not to alarm them nor to suggest that herbicides could be responsible. Eventually she found out about other miscarriages.

"I was not inquiring about spring miscarriages exclusively, but about all miscarriages in the area," says Bonnie. "Every time we heard about a miscarriage it was in the spring. One was in October (autumn) - but that year they sprayed in September, so it seemed to fit into the pattern as well."

She also placed a series of phone calls to the Bureau of Land Management, the U.S. Forest Service, in the Alsea area. She wanted to know when and where they had sprayed and what the specific sites were. She made no secret of why she was asking questions and she soon realized that some of the information may not be complete. She thought one representative was very helpful and concerned, but "others demonstrated reluctant, uncooperative attitudes. It took many telephone calls and many personal visits to elicit information," Bonnie says. In fact the EPA is still in the process of collecting details of the sprayings because two of the private companies who did the spraying will not release them.

By the spring of 1978, over two years later, she had tracked down 11 miscarriages experienced by eight women. Eight of the 11 miscarriages had occurred in 1976 and 1977, which she found out were by far the years of heaviest application of herbicides for the area. But she recorded only those miscarriages that had been verified by doctors. Most of the mothers were young women who had been raised in Alsea and whose husbands work in the timber industry.

Nine of the 11 miscarriages had occurred in the first three months of pregnancy, which coincides with the findings in the experimental animal tests.

After she had gathered all the spray data she seemed likely to get, she made up a chart listing the dates of the miscarriages, the dates of the herbicide sprayings for each agency and company, and the amounts and names of the chemicals used by each.

"I then drew up maps of exact spray sites based on the admittedly incomplete data that I had," Bonnie says, "and compared them to the location of each woman's home."

She found that the closest lived no further than two miles away. Because she wasn't given complete data she cannot help wondering if the spray sites could have been even closer.

At this point she decided the miscarriages followed the spraying so closely, and the women lived so close to the spray sites, that the facts were too strong to ignore. So she sent out a letter outlining the results and asking for help to research it further. All eight women signed the letter.

The EPA saw the beginning of some solid research on human exposure and stepped in. An agency team of doctors interviewed each of the women using a detailed 18-page questionnaire.

The results were consistent enough for the EPA to undertake a further study of the hospital records of a 1,600-square-mile area of southwest Oregon, including Alsea, over the previous six-year period. It also chose two control areas, one rural and one urban, both of which had little or no exposure to the herbicide.

The EPA found that, unlike the control areas, the 1,600-square-mile area had a remarkably high miscarriage rate and that the rate rose significantly following spray periods.

The findings were solid enough for the EPA to call an immediate emergency ban on all uses of 2,4,5-T and Silvex, except for areas where human exposure is minimal. An emergency ban is the most drastic legal move the EPA can make. One of the main reasons for this ban was to protect an estimated "4 million people across the nation [who] may be at risk through the use of the herbicide."

The EPA says the Alsea studies, taken with animal tests that show the embryo is particularly susceptible to low dosage levels early in the pregnancy, suggest "a possible relationship between the use of the pesticide and the miscarriages reported." The EPA also thinks that Alsea may not be unique. It says reports of people affected by exposure to herbicides have frequently appeared in medical and scientific journals, and the agency has received many reports itself.

The Dow Chemical Company reacted angrily to the emergency ban. UPI reported Dow Company president David Rooke as saying, "Bad science can't be left unchallenged" and "we can't let fear, distrust or special interest build emotion" which results in questionable decisions.

"This is not a chemical that can be capriciously wiped off the market. If you can take this off the market, what's safe?" Rooke asked.

In the face of the gathering evidence, his question is ominous.

* * * * *

The side-effects of spraying the herbicides on the forest in the Alsea area have left a legacy of deep scars.Debbie Morano, 25, had four miscarriages in two years. She was one of the eight women cited in Bonnie Hill's original research. She added her signature to the letter Bonnie Hill wrote that eventually led to the emergency ban on 2,4,5-T and Silvex. The Moranos live 30 miles from the Alsea township in a small valley surrounded by tree-covered hills. There are only three other houses nearby.

The walls of the small two-bedroom home have large religious tapestries and paintings on them. The doormat carries their names - "John and Debbie Welcome You" - as does a wood carving over the kitchen door, a wedding present.

Debbie Morano lost her first baby in May 1975 after 14 weeks of pregnancy. "I thought it was just one of those things," she says. "A lot of women lost their first baby, the doctor said. We believed it, why should it be wrong? We believe things, we're fine."

Debbie is small and slim with large tinted glasses. Her speech has a disjointed quality in it, as if questioning the things around her is a role she can't get used to.

"I didn't even know they were spraying," she says. And she thought, "they obviously wouldn't spray anything that is dangerous to humans. I've become very disillusioned."

By the time she'd had her fourth miscarriage, in February 1977, she knew about the spraying and she knew some people thought that the herbicides could be her problem. Her doctor had still found no explanation for them.

She contacted the EPA, which came a took samples of their elk beef shot locally, and their soil. The beef was found free of dioxyn and a chromosome test of her husband was normal, but she's not so sure about the soil.

"I've got letters that are kinda vague," she says. "They deny it but they keep a way out."

So she hasn't kept a garden since then.

Debbie finally gave birth to a son in June 1978. They called him Matthew. "It means Gift of God. We figgered that's what he was after all this fuss," Debbie says. They're moving to Alsea in November and she's glad to go although she knows the same problem is there, too.

Her stories of what has happened to herself, her neighbors and her friends have the cumulative effect of horror. Friends of her husband, a family of four, were soaked with the spray accidentally while hunting in the woods 11 years ago. The mother had menstrual problems six months after the spraying which have never normalized since. Her son, now 13, had bone cancer. When that was brought under control he developed leukemia. The mother was hospitalised with mental problems.

Debbie talked about the people in her immediate area.

"Two neighbors have had miscarriages since they started spraying with 2,4-D [a substitute for 2,4,5-T], one just across the fence, the other just across the field. Out of these four houses there's been two cases of cancer, three miscarriages, and two babies with a problem of yellow jaundice.

"My husband has migraine headaches, which he's never had before. There's just a lot of things, besides, that matter, like flu symptoms."

Each single thing in itself wouldn't have raised their suspicion. But there are so many things now they've become really suspicious.

She looked around at the view. "Everybody lives here to get away from the smog and pollution. But it just doesn't seem a nice place to live any more." She can't quite handle the contradiction. "It's almost funny if you want to be sadistic."

* * * * *

Bonnie Hill's determined investigation of the facts surrounding the miscarriages of women in the Alsea area has had profound effects on both the timber and chemical industries in the United States. It may also change the official attitude toward the experience of ordinary people.The most obvious effect is the economic impact on the timber industry. The ban means more work but fewer trees to show for it.

Foresters regard 2,4,5-T as a valuable tool because they say it is a cheap and easy way of reducing the competition of unwanted vegetation with the Douglas fir. They say the herbicide is used a total of only three or four times in the first 15 years of the firs' life. Without the herbicide, control of the surrounding vegetation is much less effective, with the result that fewer trees survive for harvesting.

Douglas Liecz, associate chief of the U.S. Forest Service, was reported as saying the ban could cost the U.S. timber industry 15 million cubic feet of lumber at a cost of $20 million a year.

An Oregon report was much bolder. It predicted a loss in Oregon alone of 936 million board feet, and it estimated that 20,000 jobs in the timber and related industries would be lost.

That report may have been too bold. A private economist, Jan Newton, criticised it in detail for its "carelessness, distortion and error." She says the report came from industry sources who inflated the likely loss of timber.

And the loss of jobs for 20,000 people, Ms Newton points out, applies to some 50 or more years in the future when the timber is actually harvested. She says the figure is "not only scientifically indefensible, but absurd."

The EPA estimates the short-term effects could be about $20 million of the first year for increased costs and yield losses, and nearly $40 million the second year. The EPA says, "While significant, these impacts are rather nominal within the context of the overall forestry industry in the United States."

The timber industry and others who support the use of the herbicides often refer to the events in Seveso, Italy, and defoliation practices in Vietnam, in favor of their case.

On July 10, 1976, a chemical plant in Seveso exploded, resulting in widespread contamination of the surrounding countryside with TCDD. Hundreds of animals died, many residents reported skin disorders, and an area of 110 hectares was evacuated.

Reports made in 1977 claim that the pollution was not as serious as feared, most patients were expected to recover completely, and pregnant women exposed to TCDD contamination at a critical stage of pregnancy "have now had their babies without any higher than average incidence of abnormality."

The EPA disagrees. In its emergency order suspending the use of 2,4,5-T it throws a somewhat different light on the aftermath of the explosion. It criticises deficiencies in the data and how it was treated and interpreted. And it quotes other evidence showing that the congenital malformation rate increased seven-fold in 1976 and the first five months of 1977. The birth rate dropped "sharply" following the explosion, and a local doctor noted a "marked increase" in convulsions among infants.

The defoliation program in Vietnam used Agent Orange, a herbicide mixture contaminated heavily with TCDD. It was aimed at completely destroying the vegetation, and was applied at four times the rate allowed in the United States by large aircraft flying several hundred feet above the ground. The highly poisonous contaminant TCDD was 25 times stronger in Agent Orange than is currently allowed in 2,4,5-T.

The events in Vietnam have made it difficult to assess what the effect of this heavy concentration of poison was on the population of Vietnam. The EPA has some evidence which suggests the defoliant affected children's health. And nearly 500 Vietnam veterans believe their contact with Agent Orange affected them. They are claiming disability benefits for problems ranging from deformed children to nervous disorders.

One of the reasons the dangers from the herbicides didn't receive close attention was the lack of knowledge about how they can spread. There are a number of ways in which the poison can be absorbed - by breathing it, eating it, drinking it, or even getting it on the skin.

At first it was thought that 2,4,5-T was not too dangerous because it soon broke down in the environment. But the contaminant TCDD, says the EPA, "has a much longer persistence in soil and is known to bioaccumulate in fish." One thing that all eight women in Bonnie Hill's research had in common was they all ate fish and game caught locally.

Recent studies have shown that the herbicide spray can drift much further than previously thought. A draft report of the EPA to Congress says the percentage of herbicide drifting more than 1,000 feet from the target area ranges from 10 percent to as much as 90 percent. And it says some of it has been reported as far as 22 miles from the target.

The only drift study made in the hilly forested area of Oregon near Alsea shows, despite optimum conditions and the observance of all restrictions, 70 percent of the herbicide found its way into a nearby stream.

The EPA found TCDD in the sediment of a stream from which one Alsea woman draws the water for her family. The woman has had two miscarriages, and her 4-year-old son, conceived during the spray season, had a history of serious respiratory problems.

Some reports on 2,4,5-T consider what they call "worst case estimates." The 1977 report made by the New Zealand Department of Health put up the example of a woman sprayed with 2,4,5-T so her entire skin surface was covered. The report concluded that the safety factor was still sizable and the intake of 2,4,5-T would be far below the "No effect level" in animal studies.

However, the concept of a "no-effect level" has been discredited. The World Health Organization and the National Research Council of Canada agree that a "no-effect level for man could not be established."

An EPA spokesman in Seattle said that TCDD, the most poisonous chemical made by man, can occur "in such minute levels that we don't have the ability to test and find it."

And speaking of Bonnie Hill's work and the investigations that followed he said, "We may have to, for a while, rely on this kind of information, these kind of probable links."

* * * * *

While Bonnie Hill is knowledgeable in this matter now, she is not a qualified expert. But in her testimony to the forest subcommittee of the U.S. House of Representatives she pleaded the cause for the evidence and the rights of the common citizen.Scientists cannot study humans in the laboratory or even in the field with the ease and control animal testing. Nevertheless, Bonnie complains, many will not take any notice of people's accounts of how they have been affected because their evidence is "anecdotal" or "circumstantial."

"Somehow, we ordinary folk are left to 'prove' that we have been adversely affected by a foreign element in our environment to which we are exposed without our consent - and whatever 'proof' we have to offer is rarely accepted," Bonnie told the subcommittee.

In the face of the difficulty in obtaining hard data such a rejection can be dangerous.

She asks, "What else is there left, besides people who are able to observe things that are happening around them, and who are able to reason that certain relationships are most certainly possible?"

Northwestern Magazine, Portland, Oregon, 1979