"We don't feel like expatriates," says 59-year old Aucklander Marie Stark. "We are New Zealanders born and bred and we chose to come over here to live with our husbands. I still have allegiance to New Zealand in my heart."

Marie Stark was speaking at a reunion of New Zealand war brides who married American servicemen stationed in New Zealand during World War Two. She organised the reunion when she saw an article on English war brides. She realised it was 40 years since they had come to the United States.

She wrote to the New Zealand Embassy's newsletter Update. The newsletter advertised her proposal for a reunion. It said American soldiers in New Zealand during World War Two reached a peak of 42,000 in mid-1943. The United States forces included two marine divisions, a base depot and a hospital. Eventually 1,400 married New Zealanders.

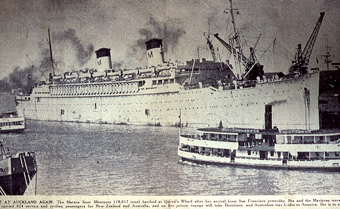

Marie got more than a dozen letters from all over the United States in response to that article. Many of the war brides, like Marie, had travelled to San Francisco on the Matson liner Monterey or its sister ship Mariposa, in 1946. Marie invited them all to meet at her house in the lush countryside of New York State.

"I called it an open house," she said. "Then I thought we'll have a buffet supper and sit around with a pot of tea and do it New Zealand style."

The gathering was small and informal. The war brides talked about the romance of being wooed by soldiers from a foreign land. And about the problems, how the war separated them, and how long and arduous the journey was to join them again.

They spoke of the shock of adjusting to a new country, and why none of them would return to live in New Zealand today. They and their husbands, who risked their lives defending New Zealand more than 40 years ago, also gave their candid reactions to New Zealand's new policy of barring nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered ships from its harbours.

"We were standing at the corner of John Court's Department Store in Queen Street and wondering what we were going to do," Louis Stark said. An elderly gentleman told them which tram to get on and said, "Go out to Crystal Palace and have a dance there."

Marie said, "Crystal Palace had a dance floor underneath and a movie theatre up above. In Mt Albert, somewhere like that. My mother and brother went to the movies and my girlfriend and I went to the dance. They played a beer barrel polka and Louis came over and wanted me to do the polka with him. The polka. That's our dance."

Stark said, "The thing is, you see, I come from an area in Nebraska where the Czech people do a lot of polka dancing."

Marie invited him home and Mrs Blair offered him a cup of tea. That was the clincher.

Stark said, "My grandmother used to make tea for me like that with milk in it years ago. And they had a nice fireplace that was warm. This was in May of 1943 so it was kind of cool and crisp then. That cup of tea and the fireplace was everything different than we had been treated in the last year or two." Stark had just come from the fighting at Guadacanal.

James Ainsworth also met his wife, Betty Fowler, at an Auckland dance hall. Betty went to dances in Victoria Park regularly. "We were chaperoned there and back," she said. "The Navy picked us up in a great big canvas-covered truck from downtown Auckland. Then after the dance was over they would take us back to that same spot."

Ainsworth played saxophone in the Army band. He saw Betty smiling at him. At the break she agreed to go to supper with him.

"Then he asked, Could he take me home?" said Betty. "And I said, Ooh, we're not allowed to go home with you. He said, I'll get permission."

Ainsworth was not a slow worker. "It seemed like it was almost meant to be," he says now. "We got out past the gate, I got my good old whistle going from my mouth, beckoned a taxicab, it came right up in big style and off we went to her home."

Joyce Graham was a shorthand typist in Wellington when war was declared. She was moved to an "essential industry" to be a costing clerk at a radio and equipment manufacturer.

Her brother had got into the habit of inviting servicemen back to the house for a meal. "They were sick and tired and yellow with malaria and no place to go and looking so forlorn," Joyce said. "My brother would bring maybe three or four home for a meal and they were so happy to be with families, you know, after being in the Islands."

One of them finished up with a photo of Joyce. Back in Noumea he showed it to James Maranville. Maranville had been wounded in action for the Carlson Raiders, the elite force that later became the Green Berets. He was being shipped to New Zealand for guard duty at Hutt Park.

Maranville studied the photo and said, "She looks all right, but she's got skinny ankles." He remembered her though, and turned up at the house one day. Afterwards he said to his friend, "That's the girl I'm going to marry."

Joyce says, "I liked him, he was very nice, but I was engaged at the time to a New Zealand serviceman so I wasn't thinking along those lines at all. I didn't see him again for a couple of months.

"Then he called up one night. I said, What happened to you? I thought you'd come back in for a meal."

Maranville told her he thought it wouldn't be fair to come back because she was engaged. But he'd decided, all's fair in love and war. "So we started dating," Joyce said. "I broke my engagement. We met in May and married in December 1943."

Many of the men were shipped out shortly after they married. The couples were not reunited for more than a year, sometimes two. Louis and Marie Stark were perhaps the luckiest. When the big push north came, the link between New Zealand and the armed forces was vital. Stark, a communications officer, got to stay in Auckland with his wife for more than a year. They rented a room from Marie's parents.

"There were four U.S. navy personnel left in Auckland - Lt Pitts, Lt Gerson, Jim Spanos from Yorksbury and myself," Stark said. "We went out on the beach one time and got some beef sirloins and had a big barbeque on the beach, picked up catseye shells." Marie still keeps a ring with a big catseye on it.

Finally Stark was sent back to the States for further training in sonar. The Japanese surrendered shortly afterwards. Stark returned to work in his home state of Nebraska and waited for his wife. It was a year before he saw her again.

Saxophonist James Ainsworth didn't mind which way it went. He was quite romantic about it. "I would do anything at that time, or any time as a matter of fact, to please my love," he said. "If she hadn't come over I would have got on a banana boat and gone back to pick her up or be with her, because that's what I planned."

Deciding to go to the States was much easier than getting there. The Eagle Club, an organisation of brides and fiancees of U.S. servicemen, agitated for months to gain passage on a ship. It took a telegram to President Harry Truman to cut through the red tape.

Una Joan Yeoman of Wellington, who married Bosun's Mate Yeoman of Torrance, California, cabled the President: "Desperate Appeal Stop Please Let Us Travel Monterey Stop New Zealand Eagles."

No one in Washington knew who the Eagles were. The U.S. State Department called the New Zealand Legation in Washington. They didn't know either. They cabled New Zealand. Within a fortnight the announcement was made - the war brides could sail in the Monterey.

The Monterey left Auckland on February 9, 1946 with 200 New Zealand war brides on board. It called into Sydney to pick up a further 600 Australian war brides before sailing on to San Francisco.

Departure time was the worst.

Catherine Taylor says, "When I left I saw my mother on the wharf put her face in her hands. I wanted to go back on shore. Luckily my brother was there with me. He said, Don't you dare turn back. He put his hands on my shoulders, turned me round and marched me down into the cabin."

For the women without babies the voyage was a lot of fun. There were movies, including The Man Who Came to Dinner, and one night they had a dress-up party.

The Red Cross helped with the entertainment on board, but their efforts weren't always appreciated. Marie Stark said disparagingly, "They had Red Cross personnel there who were going to teach New Zealanders how to knit. And they told us what we should and shouldn't wear when we got to America. I tell you, New Zealanders were seething. We were used to dressing up with our gloves and hat on when we went out. When we got to America we saw all these middle-aged women running round with bobby sox and jeans on."

For the women with babies on board there were real problems.

Joyce Maranville was married only a few weeks before the Carlson Raiders shipped her husband to Hawaii. She didn't know she was pregnant at the time. She didn't see him again for more than two years.

On the Monterey the women with children were given outside cabins with portholes, close to the sea air. But it was still decked out as a troop ship.

Joyce said, "There were three of us, three women and three children, in a very small cabin. My brother arranged the fourth set of bunks for our cabin luggage. Set it up so we could get to it and make use of it. When we were at sea a few days they took off the top layer of bunks so that it would give more room for the air to circulate. How those soldiers ever got into those top bunks, I don't know. You couldn't turn over in that top bunk. You slid in sideways and just stayed there."

On the ship she took care of her baby daughter Jill, in between bouts of seasickness. Red Cross personnel made it as easy as they could for them. But part way over they had to switch to a new American formula baby food. It didn't agree with some of the babies.

Joyce said, "Jill ended up in sick bay. She wouldn't eat the food at all. It was awful. I thought if she'd just drink her milk it'd be all right. The first solid food that she ate was in San Rafael outside the Golden Gate Bridge. She ate lima beans. She hasn't liked them from that day to this."

At least they had American disposable diapers. One officer said they must have left a string of diapers all the way from Auckland to San Francisco, because after they were used they were thrown out the portholes.

That's not all that was discarded. Joyce Maranville said, "I wanted to keep all my good undies for when I arrived in the United States, so I wore all my old holey ones. Instead of washing them, I threw them out the porthole. I thought, This is going to be hard when I get over there, I'm going to have to wash things."

A train pulled up alongside the ship on the wharf. The brides filed onto it. For those going right across America the trip lasted four nights and five days.

The closer Joan Senio got to meeting her husband, the more nervous she became. They had been married for only two weeks before he was shipped out to fight in the Philippines and New Guinea. It was now more than two years since she'd seen him.

In that time, Norbert Senio had won the Bronze Star for knocking out machine guns and mortars on the ridge on the back of Clark Field in Luzon in the Philippines. His outfit had suffered a lot of casualties.

Joan had sent him photos wearing her new suit with a New Zealand travel rug over her arm so he would recognise her when she got off the train. He knew what she'd look like. After two years she wasn't sure she'd recognise him.

"The train ride was the roughest," Joan said. "It was very crowded and we stopped at every town in America, every little town that was on the map. All through the night the train kept stopping, letting one girl off here or maybe two girls off there."

As the trip went on her fears got worse. She developed diarrhoea. She was terrified her husband wouldn't be there. "I'd see girls getting off at these different stations and there'd be nobody there to meet them," Joan said. "Poor girls, what are they going to do? And I thought that was going to happen to me."

But he met her at the station. And she recognised him right away, even without the uniform. It was the first time she'd seen him without one. Norbert Senio took Joan out of the station and showed her a big brand-new car. He said, "This is ours."

What a scene that caused.

Joan said, "We were hugging and kissing right on the sidewalk in broad daylight. Everybody was walking by thinking, What's the matter with those two, can't they find a hotel or something?"

"It wasn't that bad," said Norbert, grinning.

"They didn't realise we hadn't seen each other for two years and we had all this stored up," Joan said. "That was a true test probably, that we would stay together all these years, 42 years."

For others, the arrangements were not as straightforward.

Betty Fowler arrived in San Francisco on the Mariposa about three months after the Monterey's trip. Because she wasn't married, her fiancee, James Ainsworth, had to post a $500 bond, enough money to send her back to New Zealand. She was locked in a room all day until the money arrived. She was guarded by a Red Cross official who escorted her to lunch and the bathroom. She felt like a criminal.

Then she sent a telegram to Ainsworth in Connecticut asking him to meet her in New York on the Broadway Limited from Chicago. Unfortunately the word Limited was dropped from the message, and Broadway is one of the longest streets in the United States. When she arrived he wasn't there.

She called him up and burst into tears.

Ainsworth was mortified. He told her to catch another train up to Warehouse Point, Connecticut, about an hour away. This time he was there to meet her.

Warehouse Point is a small country town. Betty Ainsworth didn't like it at all. "I was an Auckland city girl," she says. "We had lived in the country when I was young and I didn't like it. Warehouse Point seemed like the end of nowhere. What got me through was I loved to read and I set myself up in my room and read. And I'd go for walks."

As it happened, Joan Senio had settled in the same small town, although they didn't meet for a while. Joan had a rough time of it after that first joyous meeting at the station. They had to stay with her husband's family because there was nowhere else to live.

The problem was that all the people Joan knew in New Zealand were English. Her husband was the first Polish person she'd met. She couldn't understand why the Americans were so proud of their different nationalities. She says, "It took me years to figure out why they were all saying, I'm Polish, or I'm Italian. I said, Why are you saying that? You're all Americans. Where does the Italian and the Polish come into it?"

Then she came to live with his parents who were immigrants from Poland. They had come through Ellis Island years before. They spoke Polish in the house. Joan felt like an outsider. She thought, What is this, what have I come to?

"I didn't have any friends my age," Joan says. "I didn't know anybody. My husband was working three jobs trying to get money to start a house for us and he was gone all the time. I hated it. For two years, I hated it here."

She was only 18. She wanted to work, but Norbert "put the kibosh on that". She was home in the house alone all day. He was working. His family was out working. And when they came home he was tired and went to bed and the family talked in Polish. She learnt a few Polish swear words, that's about all.

A year and a half later, Joan had her first baby. She wrote to her mother that she was still miserable. So her mother sent her an air ticket, a Pan American round-trip ticket, to come back to New Zealand until the new house was finished.

It cost her mother a lot of money, but it helped Joan get over that bad period of adjustment. When she got back to Connecticut it was still difficult because he was always working. But at least she had her own place and could do what she liked.

One day Norbert Senio said to her, "I think there's another New Zealand girl at the other end of town somewhere, would you like to meet her?" They went over and knocked on the door of Betty and James Ainsworth. Joan and Betty hit it off right away.

After that everything was fine. Finally Joan had somebody she could relate to. They've been best friends ever since. Neither of them were working so they spent a lot of time together. They had more children - Betty had three and Joan had four. They went everywhere together with the kids, picknicking and swimming at the lake.

Marie Stark settled with Louis in Fairbury in southeast Nebraska. It was a small town in a rural area and it had some small minds to go with it. Marie said, "I guess I was naive. When I called round to get my haircut and everybody said they were busy, I thought they were busy. I didn't realise I was being boycotted."

There was a lot of animosity towards war brides because the women felt the war brides had stolen their men. In fact, a local girl had turned Louis down. He'd got a Dear John letter from her.

Marie has no illusions about how lucky she was to have found happiness. "Have you ever heard the term, they're either too young or too old?" she said. "That's what we got left with in New Zealand. The ones that we thought were about our age and that we would be interested in going out with, were all in the service. They were fighting in Egypt or in the air force in Canada."

Louis credits Marie with his success in life. She encouraged him to quit his job and go to college, using the education grants offered GIs by the U.S. government. Later she urged him to apply for a job with IBM in New York State. IBM moved their four children, a cat, a dog, and all the furniture from the dry flat land of Kansas to the green rolling hills of New York State. They both thought, with pleasure, that it was just like New Zealand. They now think it was the best thing they could have ever done.

"We both came from the Depression, the results of the Depression," Marie says. "Louis's parents had walked off a beautiful farm for lack of $3,000 that the bank said it must have right away. My parents walked away from a nice home because they couldn't meet the mortgage payments during the Depression in New Zealand. So we both had this thing in mind. We both wanted a nice home, a family, and that's what we have. We are very pleased."

Louis is now retired but they still lead full lives. He works as the land assessor for local government and as a beekeeper on the side. Marie works in the Emergency Ward of the local hospital.

Norbert Senio is an inspector of combustion engineering for nuclear reactors built for the electric light companies. He won the Bronze Star fighting in the Philippines.

He says, "I think it's the most stupid damn thing I've ever heard of. Because the nuclear age is here to stay and New Zealand is not going to change it any more than the United States could change it, any more than Russia will ever change it. We might as well face it, and we have to prepare our defences in that way. We can't get away from it."

His Auckland-born wife, Joan, gave a reason they all mentioned. "We needed the Americans during the War. They saved us from the Japanese. It had got to the point that my mother said she was going to take me up into the hills and find some caves to hide in because we knew the Japanese were going to land. And bingo! - the Americans got there first.

"So now I feel, Why are they turning their backs on America, saying really we don't need you or your ships or your protection? Who's going to protect them way way down there? It's kind of far for the British to have ships down there."

Marie Stark disagreed. "I think New Zealand's stand is well taken," she says quietly. "There's no enemy coming down to annihilate New Zealand right now."

James Ainsworth's point of view is shared by most of them. "I don't think it's right that a relationship as strong as it is between the United States and New Zealand should be severed over something that could probably be ironed out," he says.

All of the war brides still feel strong ties with New Zealand. But none of them want to live there. Some of them have looked at the possibility but they eventually rejected it.

Norbert Senio said, "I think it cured us pretty well when we went back in 1970 when Joan's mother passed away. We found out that things in New Zealand were not the same. Everything was changed. The people we knew were gone, you can't find them. You're going to a country where you're a stranger and you have to make new friends."

And they were no longer used to the style of living. "I couldn't take the dampness in the house after being here with the central heating," Joan says.

The overriding reason keeping them all in the States is the link with their children. Joyce Maranville has kept her New Zealand citizenship, but says she'd never go back to settle. "I've got six children. They're all here and they live close by. I lost my husband two and a half years ago when we were on a trip to New Zealand and it's been wonderful for me to have my family close around me, and the grandchildren."

Marion and Willis Avery arrive later in the day. He is one of the survivors of the battleship Arizona that was sunk in Pearl Harbor. Dunedin-born Joyce Young phones from San Marcos, California. Marie tells her, "There are no South Islanders here, mostly Auckland girls."

For all of them the reunion is a time of reassessment, a time to look at their lives and see what they'd done. Joan Senio says, "We have four children and four grandchildren. I think I did pretty good by America. I gave America quite a bit. They're all Yankee Doodles."

Perhaps Betty Ainsworth says it best. "I'm proud of being a war bride and I'm proud of being a New Zealander. I have no regrets. Except the longing for home will never leave but that's something that anybody who loves their country would have wherever they were."

Her voice becomes a little tremulous. "I still think of myself as a New Zealander. I do. I'll never be anything else."

Sunday Times, New Zealand, 1986

[You can listen to them tell their stories here.]

Marie Stark was speaking at a reunion of New Zealand war brides who married American servicemen stationed in New Zealand during World War Two. She organised the reunion when she saw an article on English war brides. She realised it was 40 years since they had come to the United States.

She wrote to the New Zealand Embassy's newsletter Update. The newsletter advertised her proposal for a reunion. It said American soldiers in New Zealand during World War Two reached a peak of 42,000 in mid-1943. The United States forces included two marine divisions, a base depot and a hospital. Eventually 1,400 married New Zealanders.

Marie got more than a dozen letters from all over the United States in response to that article. Many of the war brides, like Marie, had travelled to San Francisco on the Matson liner Monterey or its sister ship Mariposa, in 1946. Marie invited them all to meet at her house in the lush countryside of New York State.

"I called it an open house," she said. "Then I thought we'll have a buffet supper and sit around with a pot of tea and do it New Zealand style."

The gathering was small and informal. The war brides talked about the romance of being wooed by soldiers from a foreign land. And about the problems, how the war separated them, and how long and arduous the journey was to join them again.

They spoke of the shock of adjusting to a new country, and why none of them would return to live in New Zealand today. They and their husbands, who risked their lives defending New Zealand more than 40 years ago, also gave their candid reactions to New Zealand's new policy of barring nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered ships from its harbours.

* * * * *

Louis Stark remembers quite clearly how he met his future wife, Marie Blair. He had just arrived in Mechanics Bay in Auckland in 1943 and went out on his first liberty with a friend."We were standing at the corner of John Court's Department Store in Queen Street and wondering what we were going to do," Louis Stark said. An elderly gentleman told them which tram to get on and said, "Go out to Crystal Palace and have a dance there."

Marie said, "Crystal Palace had a dance floor underneath and a movie theatre up above. In Mt Albert, somewhere like that. My mother and brother went to the movies and my girlfriend and I went to the dance. They played a beer barrel polka and Louis came over and wanted me to do the polka with him. The polka. That's our dance."

Stark said, "The thing is, you see, I come from an area in Nebraska where the Czech people do a lot of polka dancing."

Marie invited him home and Mrs Blair offered him a cup of tea. That was the clincher.

Stark said, "My grandmother used to make tea for me like that with milk in it years ago. And they had a nice fireplace that was warm. This was in May of 1943 so it was kind of cool and crisp then. That cup of tea and the fireplace was everything different than we had been treated in the last year or two." Stark had just come from the fighting at Guadacanal.

James Ainsworth also met his wife, Betty Fowler, at an Auckland dance hall. Betty went to dances in Victoria Park regularly. "We were chaperoned there and back," she said. "The Navy picked us up in a great big canvas-covered truck from downtown Auckland. Then after the dance was over they would take us back to that same spot."

Ainsworth played saxophone in the Army band. He saw Betty smiling at him. At the break she agreed to go to supper with him.

"Then he asked, Could he take me home?" said Betty. "And I said, Ooh, we're not allowed to go home with you. He said, I'll get permission."

Ainsworth was not a slow worker. "It seemed like it was almost meant to be," he says now. "We got out past the gate, I got my good old whistle going from my mouth, beckoned a taxicab, it came right up in big style and off we went to her home."

Joyce Graham was a shorthand typist in Wellington when war was declared. She was moved to an "essential industry" to be a costing clerk at a radio and equipment manufacturer.

Her brother had got into the habit of inviting servicemen back to the house for a meal. "They were sick and tired and yellow with malaria and no place to go and looking so forlorn," Joyce said. "My brother would bring maybe three or four home for a meal and they were so happy to be with families, you know, after being in the Islands."

One of them finished up with a photo of Joyce. Back in Noumea he showed it to James Maranville. Maranville had been wounded in action for the Carlson Raiders, the elite force that later became the Green Berets. He was being shipped to New Zealand for guard duty at Hutt Park.

Maranville studied the photo and said, "She looks all right, but she's got skinny ankles." He remembered her though, and turned up at the house one day. Afterwards he said to his friend, "That's the girl I'm going to marry."

Joyce says, "I liked him, he was very nice, but I was engaged at the time to a New Zealand serviceman so I wasn't thinking along those lines at all. I didn't see him again for a couple of months.

"Then he called up one night. I said, What happened to you? I thought you'd come back in for a meal."

Maranville told her he thought it wouldn't be fair to come back because she was engaged. But he'd decided, all's fair in love and war. "So we started dating," Joyce said. "I broke my engagement. We met in May and married in December 1943."

Many of the men were shipped out shortly after they married. The couples were not reunited for more than a year, sometimes two. Louis and Marie Stark were perhaps the luckiest. When the big push north came, the link between New Zealand and the armed forces was vital. Stark, a communications officer, got to stay in Auckland with his wife for more than a year. They rented a room from Marie's parents.

"There were four U.S. navy personnel left in Auckland - Lt Pitts, Lt Gerson, Jim Spanos from Yorksbury and myself," Stark said. "We went out on the beach one time and got some beef sirloins and had a big barbeque on the beach, picked up catseye shells." Marie still keeps a ring with a big catseye on it.

Finally Stark was sent back to the States for further training in sonar. The Japanese surrendered shortly afterwards. Stark returned to work in his home state of Nebraska and waited for his wife. It was a year before he saw her again.

* * * * *

When the war was over, it seemed natural for the women to follow their husbands to the States. As Rotorua-born Catherine Taylor puts it, "The employment opportunities in New Zealand were nil, let's say, compared with what they were in the States."Saxophonist James Ainsworth didn't mind which way it went. He was quite romantic about it. "I would do anything at that time, or any time as a matter of fact, to please my love," he said. "If she hadn't come over I would have got on a banana boat and gone back to pick her up or be with her, because that's what I planned."

Deciding to go to the States was much easier than getting there. The Eagle Club, an organisation of brides and fiancees of U.S. servicemen, agitated for months to gain passage on a ship. It took a telegram to President Harry Truman to cut through the red tape.

Una Joan Yeoman of Wellington, who married Bosun's Mate Yeoman of Torrance, California, cabled the President: "Desperate Appeal Stop Please Let Us Travel Monterey Stop New Zealand Eagles."

No one in Washington knew who the Eagles were. The U.S. State Department called the New Zealand Legation in Washington. They didn't know either. They cabled New Zealand. Within a fortnight the announcement was made - the war brides could sail in the Monterey.

The Monterey left Auckland on February 9, 1946 with 200 New Zealand war brides on board. It called into Sydney to pick up a further 600 Australian war brides before sailing on to San Francisco.

Departure time was the worst.

Catherine Taylor says, "When I left I saw my mother on the wharf put her face in her hands. I wanted to go back on shore. Luckily my brother was there with me. He said, Don't you dare turn back. He put his hands on my shoulders, turned me round and marched me down into the cabin."

For the women without babies the voyage was a lot of fun. There were movies, including The Man Who Came to Dinner, and one night they had a dress-up party.

The Red Cross helped with the entertainment on board, but their efforts weren't always appreciated. Marie Stark said disparagingly, "They had Red Cross personnel there who were going to teach New Zealanders how to knit. And they told us what we should and shouldn't wear when we got to America. I tell you, New Zealanders were seething. We were used to dressing up with our gloves and hat on when we went out. When we got to America we saw all these middle-aged women running round with bobby sox and jeans on."

For the women with babies on board there were real problems.

Joyce Maranville was married only a few weeks before the Carlson Raiders shipped her husband to Hawaii. She didn't know she was pregnant at the time. She didn't see him again for more than two years.

On the Monterey the women with children were given outside cabins with portholes, close to the sea air. But it was still decked out as a troop ship.

Joyce said, "There were three of us, three women and three children, in a very small cabin. My brother arranged the fourth set of bunks for our cabin luggage. Set it up so we could get to it and make use of it. When we were at sea a few days they took off the top layer of bunks so that it would give more room for the air to circulate. How those soldiers ever got into those top bunks, I don't know. You couldn't turn over in that top bunk. You slid in sideways and just stayed there."

On the ship she took care of her baby daughter Jill, in between bouts of seasickness. Red Cross personnel made it as easy as they could for them. But part way over they had to switch to a new American formula baby food. It didn't agree with some of the babies.

Joyce said, "Jill ended up in sick bay. She wouldn't eat the food at all. It was awful. I thought if she'd just drink her milk it'd be all right. The first solid food that she ate was in San Rafael outside the Golden Gate Bridge. She ate lima beans. She hasn't liked them from that day to this."

At least they had American disposable diapers. One officer said they must have left a string of diapers all the way from Auckland to San Francisco, because after they were used they were thrown out the portholes.

That's not all that was discarded. Joyce Maranville said, "I wanted to keep all my good undies for when I arrived in the United States, so I wore all my old holey ones. Instead of washing them, I threw them out the porthole. I thought, This is going to be hard when I get over there, I'm going to have to wash things."

* * * * *

Finally they reached San Francisco. "Some of the people remember coming into San Francisco and how rough it was," Marie Stark says. "All I remember was looking up at the Golden Gate Bridge and thinking, It's just orange paint. I thought they could have rustled up a bit of gold paint."A train pulled up alongside the ship on the wharf. The brides filed onto it. For those going right across America the trip lasted four nights and five days.

The closer Joan Senio got to meeting her husband, the more nervous she became. They had been married for only two weeks before he was shipped out to fight in the Philippines and New Guinea. It was now more than two years since she'd seen him.

In that time, Norbert Senio had won the Bronze Star for knocking out machine guns and mortars on the ridge on the back of Clark Field in Luzon in the Philippines. His outfit had suffered a lot of casualties.

Joan had sent him photos wearing her new suit with a New Zealand travel rug over her arm so he would recognise her when she got off the train. He knew what she'd look like. After two years she wasn't sure she'd recognise him.

"The train ride was the roughest," Joan said. "It was very crowded and we stopped at every town in America, every little town that was on the map. All through the night the train kept stopping, letting one girl off here or maybe two girls off there."

As the trip went on her fears got worse. She developed diarrhoea. She was terrified her husband wouldn't be there. "I'd see girls getting off at these different stations and there'd be nobody there to meet them," Joan said. "Poor girls, what are they going to do? And I thought that was going to happen to me."

But he met her at the station. And she recognised him right away, even without the uniform. It was the first time she'd seen him without one. Norbert Senio took Joan out of the station and showed her a big brand-new car. He said, "This is ours."

What a scene that caused.

Joan said, "We were hugging and kissing right on the sidewalk in broad daylight. Everybody was walking by thinking, What's the matter with those two, can't they find a hotel or something?"

"It wasn't that bad," said Norbert, grinning.

"They didn't realise we hadn't seen each other for two years and we had all this stored up," Joan said. "That was a true test probably, that we would stay together all these years, 42 years."

For others, the arrangements were not as straightforward.

Betty Fowler arrived in San Francisco on the Mariposa about three months after the Monterey's trip. Because she wasn't married, her fiancee, James Ainsworth, had to post a $500 bond, enough money to send her back to New Zealand. She was locked in a room all day until the money arrived. She was guarded by a Red Cross official who escorted her to lunch and the bathroom. She felt like a criminal.

Then she sent a telegram to Ainsworth in Connecticut asking him to meet her in New York on the Broadway Limited from Chicago. Unfortunately the word Limited was dropped from the message, and Broadway is one of the longest streets in the United States. When she arrived he wasn't there.

She called him up and burst into tears.

Ainsworth was mortified. He told her to catch another train up to Warehouse Point, Connecticut, about an hour away. This time he was there to meet her.

Warehouse Point is a small country town. Betty Ainsworth didn't like it at all. "I was an Auckland city girl," she says. "We had lived in the country when I was young and I didn't like it. Warehouse Point seemed like the end of nowhere. What got me through was I loved to read and I set myself up in my room and read. And I'd go for walks."

As it happened, Joan Senio had settled in the same small town, although they didn't meet for a while. Joan had a rough time of it after that first joyous meeting at the station. They had to stay with her husband's family because there was nowhere else to live.

The problem was that all the people Joan knew in New Zealand were English. Her husband was the first Polish person she'd met. She couldn't understand why the Americans were so proud of their different nationalities. She says, "It took me years to figure out why they were all saying, I'm Polish, or I'm Italian. I said, Why are you saying that? You're all Americans. Where does the Italian and the Polish come into it?"

Then she came to live with his parents who were immigrants from Poland. They had come through Ellis Island years before. They spoke Polish in the house. Joan felt like an outsider. She thought, What is this, what have I come to?

"I didn't have any friends my age," Joan says. "I didn't know anybody. My husband was working three jobs trying to get money to start a house for us and he was gone all the time. I hated it. For two years, I hated it here."

She was only 18. She wanted to work, but Norbert "put the kibosh on that". She was home in the house alone all day. He was working. His family was out working. And when they came home he was tired and went to bed and the family talked in Polish. She learnt a few Polish swear words, that's about all.

A year and a half later, Joan had her first baby. She wrote to her mother that she was still miserable. So her mother sent her an air ticket, a Pan American round-trip ticket, to come back to New Zealand until the new house was finished.

It cost her mother a lot of money, but it helped Joan get over that bad period of adjustment. When she got back to Connecticut it was still difficult because he was always working. But at least she had her own place and could do what she liked.

One day Norbert Senio said to her, "I think there's another New Zealand girl at the other end of town somewhere, would you like to meet her?" They went over and knocked on the door of Betty and James Ainsworth. Joan and Betty hit it off right away.

After that everything was fine. Finally Joan had somebody she could relate to. They've been best friends ever since. Neither of them were working so they spent a lot of time together. They had more children - Betty had three and Joan had four. They went everywhere together with the kids, picknicking and swimming at the lake.

Marie Stark settled with Louis in Fairbury in southeast Nebraska. It was a small town in a rural area and it had some small minds to go with it. Marie said, "I guess I was naive. When I called round to get my haircut and everybody said they were busy, I thought they were busy. I didn't realise I was being boycotted."

There was a lot of animosity towards war brides because the women felt the war brides had stolen their men. In fact, a local girl had turned Louis down. He'd got a Dear John letter from her.

Marie has no illusions about how lucky she was to have found happiness. "Have you ever heard the term, they're either too young or too old?" she said. "That's what we got left with in New Zealand. The ones that we thought were about our age and that we would be interested in going out with, were all in the service. They were fighting in Egypt or in the air force in Canada."

Louis credits Marie with his success in life. She encouraged him to quit his job and go to college, using the education grants offered GIs by the U.S. government. Later she urged him to apply for a job with IBM in New York State. IBM moved their four children, a cat, a dog, and all the furniture from the dry flat land of Kansas to the green rolling hills of New York State. They both thought, with pleasure, that it was just like New Zealand. They now think it was the best thing they could have ever done.

"We both came from the Depression, the results of the Depression," Marie says. "Louis's parents had walked off a beautiful farm for lack of $3,000 that the bank said it must have right away. My parents walked away from a nice home because they couldn't meet the mortgage payments during the Depression in New Zealand. So we both had this thing in mind. We both wanted a nice home, a family, and that's what we have. We are very pleased."

Louis is now retired but they still lead full lives. He works as the land assessor for local government and as a beekeeper on the side. Marie works in the Emergency Ward of the local hospital.

* * * * *

Very few of them agree with New Zealand's decision to ban nuclear-armed and nuclear-powered ships from its harbors.Norbert Senio is an inspector of combustion engineering for nuclear reactors built for the electric light companies. He won the Bronze Star fighting in the Philippines.

He says, "I think it's the most stupid damn thing I've ever heard of. Because the nuclear age is here to stay and New Zealand is not going to change it any more than the United States could change it, any more than Russia will ever change it. We might as well face it, and we have to prepare our defences in that way. We can't get away from it."

His Auckland-born wife, Joan, gave a reason they all mentioned. "We needed the Americans during the War. They saved us from the Japanese. It had got to the point that my mother said she was going to take me up into the hills and find some caves to hide in because we knew the Japanese were going to land. And bingo! - the Americans got there first.

"So now I feel, Why are they turning their backs on America, saying really we don't need you or your ships or your protection? Who's going to protect them way way down there? It's kind of far for the British to have ships down there."

Marie Stark disagreed. "I think New Zealand's stand is well taken," she says quietly. "There's no enemy coming down to annihilate New Zealand right now."

James Ainsworth's point of view is shared by most of them. "I don't think it's right that a relationship as strong as it is between the United States and New Zealand should be severed over something that could probably be ironed out," he says.

All of the war brides still feel strong ties with New Zealand. But none of them want to live there. Some of them have looked at the possibility but they eventually rejected it.

Norbert Senio said, "I think it cured us pretty well when we went back in 1970 when Joan's mother passed away. We found out that things in New Zealand were not the same. Everything was changed. The people we knew were gone, you can't find them. You're going to a country where you're a stranger and you have to make new friends."

And they were no longer used to the style of living. "I couldn't take the dampness in the house after being here with the central heating," Joan says.

The overriding reason keeping them all in the States is the link with their children. Joyce Maranville has kept her New Zealand citizenship, but says she'd never go back to settle. "I've got six children. They're all here and they live close by. I lost my husband two and a half years ago when we were on a trip to New Zealand and it's been wonderful for me to have my family close around me, and the grandchildren."

* * * * *

Marion and Willis Avery arrive later in the day. He is one of the survivors of the battleship Arizona that was sunk in Pearl Harbor. Dunedin-born Joyce Young phones from San Marcos, California. Marie tells her, "There are no South Islanders here, mostly Auckland girls."

For all of them the reunion is a time of reassessment, a time to look at their lives and see what they'd done. Joan Senio says, "We have four children and four grandchildren. I think I did pretty good by America. I gave America quite a bit. They're all Yankee Doodles."

Perhaps Betty Ainsworth says it best. "I'm proud of being a war bride and I'm proud of being a New Zealander. I have no regrets. Except the longing for home will never leave but that's something that anybody who loves their country would have wherever they were."

Her voice becomes a little tremulous. "I still think of myself as a New Zealander. I do. I'll never be anything else."

Sunday Times, New Zealand, 1986

[You can listen to them tell their stories here.]

Louis Stark and Marie, nee Blair

James Ainsworth and Betty, nee Fowler

Joyce Maranville, nee Graham

Norbert Senio and Joan, nee Smith.