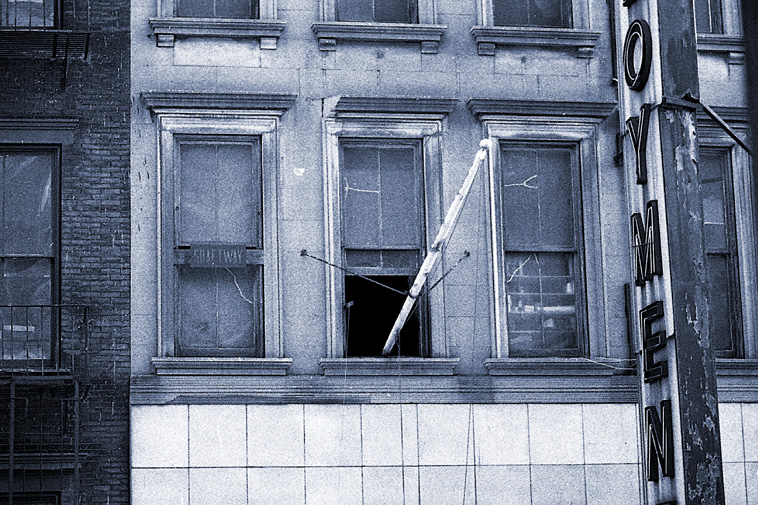

It was the summer of 1980 in Tribeca, the lower tip of Manhattan Island in New York. Directly opposite us, but the next floor up, on the third floor, lived a gray and black striped cat, a Tiger cat. He lived in a room with a window that had a flagpole sticking out of it at a 45–degree angle. Because of the flagpole, the window was always wide open, no matter the weather. The flagpole was covered with peeling white paint and had a shiny gold round tip. A thin rope, black with age, was attached to it.

A torn orange curtain dangled on one side of the window, and a rope ran down from the other side to the street door. It acted as a clumsy bell-pull to announce visitors. When the rope was pulled the cat's owner, a serious tousled-haired young man, came to the window and threw down the door key if he wanted them to come in.

Every day as I worked at my desk by my window, I would look across and the cat was there, perched on the windowsill, looking curiously down at the street, far too far below for him to go. Or he would be licking or grooming himself. Or, most often, he would be asleep in the sun on the hot concrete windowsill.

One day when I looked over he seemed livelier than usual. His ears were pricked up and his eyes were darting here and there at the goings-on in the street below.

The cat yawned, stretched, then casually strode to the left along the narrow sill three stories up, and jumped onto the next one. With hardly a pause, he half-stepped and half leapt through space through narrow iron railings onto the iron fire escape of the brick building next door. It was done with supreme assurance, even though he had to leap onto a floor made up of iron bars with a considerable gap, for a cat, between them.

At this point Helen had joined me and she couldn't resist calling out, "Puss, puss, puss." The cat paused in its journey and looked around. He didn't look across the road at us but back where he had come from. He turned round and quickly made the same trip back. When he got back to the windowsill with the flagpole poking out of it, he leapt straight into the blackness of the room beyond.

I decided he must have been hungry and was going to do a bit of hunting on his own account, before he was mistakenly called back by Helen's misplaced enthusiasm.

I was pleased by his casual grace and his cheek in setting out on such a journey. I was also intrigued and wondered where he would have ended up. I was even a little annoyed at Helen interfering and stopping him before his journey had scarcely begun.

It was nothing to start an argument about and a few days later my curiosity was – partly – satisfied.

I was working at my desk as usual. As I looked across the street at the only point of interest in the blank face of the concrete building opposite – the black open window – the cat appeared again. He wasted no time. It looked like he had made the journey many times before.

He crossed the gap between the two buildings with ease. Once on the fire escape landing he didn't hesitate. He lithely skipped up the near-vertical iron ladder to the landing above.

At the top he paused, looked in one of the blank windows, licked himself briefly, then turned and walked along the fire escape landing back the way he had come, only now he was one floor higher.

At the end of the landing he paused, then jumped down on top of the clumsily ornate concrete overhang above the third-floor windows of his own building. He strolled along the top of the windows and behind a long disused neon sign that ran down nearly the full length of the five-storey building. The letters of the word "Employment" were picked out in white neon tubing framed in rusty red iron.

Back at this end of the building it was just a small leap onto the overhang of the roof of the dingy three-storey building next door. His tail made an arc over the blue sky and he disappeared from sight.

His leap made a sudden emptiness. I was sure I would never see him again. I knew only a small part of where his adventurous spirit would take him. The mystery of what would happen to him consumed me and made me restless for some time.

Mary, the older of the two, was much more wary. She came in once or twice but only when we were out. We'd catch her scurrying for the fire balcony when we came home from a night out. Her curiosity was soon satisfied and she kept a discreet distance. She didn't want to get to know two new humans just yet, thank you.

Cordy was different. She was still nearly a kitten with pretty white and ginger patches. She was terribly shy but she couldn't resist coming in to see what was happening, or whether that piece of yellow ribbon fluttering from the end of my fingers was really alive and maybe worth eating.

Once she woke us up in the middle of the night walking over our bed and squealing her plaintive meow. When we moved she scampered off again.

A few nights later her behavior changed. She appeared at the witching hour again but she was restless. She kept pacing backwards and forwards over the bed and around the side. Every so often she came up to Helen's face and touched it gently with her nose and whiskers - Helen's eyes, nose and mouth. She kept being drawn back to our bed in the farthest, darkest corner of the apartment as if by a magnet.

Helen finally pushed her down to the bottom of the bed where she sat huddled up with wide eyes. Helen claims she felt the cat looking at her all night. Her dreams about the cat disturbed her sleep.

In the morning Cordy was still there, sitting on the end of the bed, its wide eyes looking at us, not comfortable and relaxed, yet not wanting to move.

Finally it was time to get up and we decided it was time Cordy went home too. We didn't mind her being there but she wasn't ours and the woman next door might be getting worried.

So Helen picked her up and took her down the steps from the landing, over to the fire balcony, and put her out the door. Cordy wasn't having any of it. Her ears went back, her eyes went wider still, and as soon as she was released she scampered back across the floor, shot up the steps to our mezzanine floor and plonked herself on our bed again. When I went up to her she looked at me defiantly and a little piteously too.

I said to Helen, "She must have had a fright on the balcony last night and is scared to go back across it. I'll shut the door on her so she'll have to discover that whatever scared her has gone."

I was quite wrong. As soon as she found she was trapped on the balcony, she leapt on our windowsill and crawled along it as far as she could go. She looked quite crazy and frantic, jerking her head around nervously at every noise.

It was far too worrying to see here there. She could fall – or jump - to the street in her wild state. I opened the door and called her back in.

I picked her up and cradled her in my arms. She accepted the gesture, her little heart beating furiously.

Nevertheless she had to go back to her owner. I took her out to the corridor. Her ears pricked up. Her head and eyes alertly scanned the hallway. I thought, she hasn't been out here before, she's wondering what's happening.

Her owner answered the door and let me in. Immediately the mystery was solved. A large young amiable Airedale dog loped up to us.

Cordy freaked. Her fur stood on end. She raced up my right arm and onto my shoulders. She took a panic-stricken leap at the stairs leading up to her owner's mezzanine landing. In her haste she misjudged her footing. She tumbled and rolled down half a dozen stairs before her claws dug in and stopped her. She flipped herself up and was out of sight in a flash.

My arm, neck and shoulders received a few scratches but nothing serious.

The woman told me Cordy would hide in the back of her darkest deepest closet. The dog had arrived the night before and the woman was looking after it for a month.

The other cat, Mary, had quickly worked out an arrangement where she ignored the dog and the dog kept its distance. Cordy hadn't acquired enough maturity and experience to be able to do the same. The dog was friendly but its size and smell overwhelmed poor Cordy.

I told the woman about the cat across the road, and that I hadn't seen it since. She said, "It won't be back. That was a nice cat too."

That's what I thought, but we were both wrong. The cat came back. I saw it yesterday, sitting on the window ledge sunning itself and licking its fur. It was thinner than I remembered it, and its black stripes seemed darker, more prominent. It gave me pleasure to see it. Except the old questions rose again in my mind. Where did it go? What did it do? And a new, more engrossing and immediate question: Will I see it go away again?

The cat lived on the third floor of a dirty grey five-storey building made of concrete. Like all the other buildings on that side of Warren Street it was a dingy narrow place well past its prime. Years of the city's dirt and soot clung to its façade.

It used to be an employment office. Now the top two floors were empty, the next two down were each occupied by an artist and a musician, and the ground floor was used to store the local street-vendors' handcarts overnight.

Four narrow windows were crammed along the frontage and the builders used these in a crude attempt to pretty up the place. The window ledges were made of pre-molded concrete and had two little footings at each end, like vertical bookends. The tops of the windows were even uglier. They were similar in design to the sills but thicker and heavier, and longer too. Whereas the window ledges had a foot-and-a-half gap between them, the overhangs on top nearly touched each other.

Both features had their uses. To the cat they were as broad as the roadway below. He trotted along them with assurance on his journeys up and down the face of the buildings. He was like a rock-climbing enthusiast. He had conquered all the vertical territory from the third floor windowsills up to the top floor, not only of his own building but of the narrow brick building to the left. He had also found a way to the roof of the three-storey apartment house on the right.

To me his journeys were as exciting and unexpected as trapeze artists and high-wire walkers in the circus. Except the cat had no ropes nor safety net.

The grimy windows on the third floor masked the room beyond. One of the windows was always open because of a dirty white flagpole poking out of it like a jaunty cigarette in the mouth of a gap-toothed bum. The open window revealed nothing. It was a black impenetrable hole. It's always from this window that the cat began its adventurous journeys.

The longest and most adventurous journey I saw the cat make began one morning when he leapt out of the blackness of his room onto the windowsill. He paused, as if taking a bow, then strolled along the windowsills towards the brick building on the left.

There is a three-foot gap between the windowsill and the wrought-iron fire escape on the brick building. There is also an iron railing around the fire balcony, with vertical guards about eight inches apart. To get from his building to the next, he had to jump a three-foot gap from the window ledge to the wrought-iron fire balcony on the brick building. He had to pass through the eight-inch gaps in the iron supports of the railing. And he had to land on a floor of flat, spaced-out iron bars. Not the best surface to land on even for a sure-footed cat.

It was like watching a circus lion jump through a hoop, except this hoop was 40 feet above the street. Yet it was all done with the nonchalance of someone travelling a difficult yet familiar road.

The cat picked his way sure-footedly over the iron bars of the fire balcony, then ran up the near-vertical iron ladder to the next landing above. It was done in two short sharp sprints. The steps were two close-set iron bars. The cat climbed by using his forepaws rather than his pads. When he paused, halfway up, his paws hung over the edge of the steps like the hands of a man leaning on his forearms on a railing.

This took the cat up the fire balcony on the fourth floor of the brick building next door. He cautiously went to one end of the balcony, just sniffing around. Then he returned to the ladder … and did the same trick again, up to the fifth floor.

This time he walked back towards his own place. When he reached the end of the fire balcony, he poked his head through the rails – and jumped.

His leap took him onto the highway of the thick ugly concrete overhangs that topped off the fourth floor windows of his own building. He prowled slowly along. The white droppings of pigeons could be seen dribbling over the edge.

When he came to the end of the second overhang he stopped. He looked up at the windowsills above, the windowsills of the fifth floor. He was about 60 feet up from the street, but he didn't look down. He seemed much more curious about how much further up he could go.

His mind was made up. At the same moment, not hurriedly but with grace and conviction, he gathered his limbs together and leapt upwards.

It was a breathtaking moment. Here he was clinging to a narrow ledge high above the concrete sidewalk below. Then, without any apparent thought and with utmost confidence, he made a lazy leap skywards to an even narrower ledge three or four feet higher.

It took a fraction of time. A flash of complete concentration and he had arrived. He disappeared through a broken pane in the fifth floor window.

The memory of that magical leap lingered on. It was a rare feat, and one that it looked like he'd never be able to repeat. But that's getting ahead of my story.

I now knew what was driving him on. I'd often seen him on the comparative safety of his own windowsill looking intently across and down. I'd follow his line of sight and he was always interested in a pigeon waddling around on the street below. He also watched them on the windowsills above him. He knew their favorite roosting places. He wanted to try out his hunting luck.

Suddenly there was a flurry of feathers. He rose in the air and dropped down onto her back. A few moments and it was all over.

The female started preening herself while he strutted to the end of the window ledge.

At this point I was about to return to my work when the male pigeon flew off the ledge onto the roof of the three-storey building to the right. He landed on the edge of the roof, then sidled back a little, out of sight of the windowsills.

Here I laughed out loud. Only minutes after his previous conquest, he started going through the same ritual with another female pigeon. But out of sight of the other, as if he didn't want to get a reputation as a fickle lover.

This time when I noticed him, he was on top of the windows on the third floor, his floor, but a level too high. It looked like he had just returned from the roof of the three-storey building on the right.

His movements were much more exploratory and tentative. He was heading downwards towards home this time. He could see how far he would fall if he missed his target.

He crept behind the long, disused vertical neon sign that ran down the full length of the building. It advertised an Employment Agency that once operated there.

It was a bulky sign, and it soon became apparent that it was hollow. For the cat finally made his decision and jumped down inside it.

This trick took him about a quarter way down the length of the windows. It was also probably a roosting place of the pigeons, particularly in bad weather. As they had led him up to the fifth floor, it seemed appropriate that they should show him the way back down as well.

The cat's head poked out from the back of the sign. He was still in trouble. Although he had found a safe ledge, he was still a good five feet up from the third-floor windowsills.

He cautiously inched his body out of the sign. His forepaws crept down the outside of his perch. His eyes looked anxiously down at the sill. So near, yet still a large – and dangerous – jump, to home.

He teetered out as far as he could without actually letting go. Then, gathering his resources, he sprang.

His tail stuck straight up from his backside. It acted as a balance and even perhaps as a partial air brake. The rigidity of the erect tail betrayed the tension of the jump.

He landed safely and immediately trotted along the windowsills to his own open window. His tail trailed languidly behind him.

He casually sprang out of sight and disappeared. The transformation from tense effort to casual insouciance was instantaneous. Once done he gave it no further thought.

1980

A torn orange curtain dangled on one side of the window, and a rope ran down from the other side to the street door. It acted as a clumsy bell-pull to announce visitors. When the rope was pulled the cat's owner, a serious tousled-haired young man, came to the window and threw down the door key if he wanted them to come in.

Every day as I worked at my desk by my window, I would look across and the cat was there, perched on the windowsill, looking curiously down at the street, far too far below for him to go. Or he would be licking or grooming himself. Or, most often, he would be asleep in the sun on the hot concrete windowsill.

One day when I looked over he seemed livelier than usual. His ears were pricked up and his eyes were darting here and there at the goings-on in the street below.

The cat yawned, stretched, then casually strode to the left along the narrow sill three stories up, and jumped onto the next one. With hardly a pause, he half-stepped and half leapt through space through narrow iron railings onto the iron fire escape of the brick building next door. It was done with supreme assurance, even though he had to leap onto a floor made up of iron bars with a considerable gap, for a cat, between them.

At this point Helen had joined me and she couldn't resist calling out, "Puss, puss, puss." The cat paused in its journey and looked around. He didn't look across the road at us but back where he had come from. He turned round and quickly made the same trip back. When he got back to the windowsill with the flagpole poking out of it, he leapt straight into the blackness of the room beyond.

I decided he must have been hungry and was going to do a bit of hunting on his own account, before he was mistakenly called back by Helen's misplaced enthusiasm.

I was pleased by his casual grace and his cheek in setting out on such a journey. I was also intrigued and wondered where he would have ended up. I was even a little annoyed at Helen interfering and stopping him before his journey had scarcely begun.

It was nothing to start an argument about and a few days later my curiosity was – partly – satisfied.

I was working at my desk as usual. As I looked across the street at the only point of interest in the blank face of the concrete building opposite – the black open window – the cat appeared again. He wasted no time. It looked like he had made the journey many times before.

He crossed the gap between the two buildings with ease. Once on the fire escape landing he didn't hesitate. He lithely skipped up the near-vertical iron ladder to the landing above.

At the top he paused, looked in one of the blank windows, licked himself briefly, then turned and walked along the fire escape landing back the way he had come, only now he was one floor higher.

At the end of the landing he paused, then jumped down on top of the clumsily ornate concrete overhang above the third-floor windows of his own building. He strolled along the top of the windows and behind a long disused neon sign that ran down nearly the full length of the five-storey building. The letters of the word "Employment" were picked out in white neon tubing framed in rusty red iron.

Back at this end of the building it was just a small leap onto the overhang of the roof of the dingy three-storey building next door. His tail made an arc over the blue sky and he disappeared from sight.

His leap made a sudden emptiness. I was sure I would never see him again. I knew only a small part of where his adventurous spirit would take him. The mystery of what would happen to him consumed me and made me restless for some time.

* * * * *

Fortunately the cats belonging to the woman next door diverted my interest. She had just moved in and her two cats were cautiously exploring the boundaries of their new existence. They soon discovered the fire balcony, and that we always kept the door to it open as much as possible to take advantage of the cooling breeze coming off the Hudson River.Mary, the older of the two, was much more wary. She came in once or twice but only when we were out. We'd catch her scurrying for the fire balcony when we came home from a night out. Her curiosity was soon satisfied and she kept a discreet distance. She didn't want to get to know two new humans just yet, thank you.

Cordy was different. She was still nearly a kitten with pretty white and ginger patches. She was terribly shy but she couldn't resist coming in to see what was happening, or whether that piece of yellow ribbon fluttering from the end of my fingers was really alive and maybe worth eating.

Once she woke us up in the middle of the night walking over our bed and squealing her plaintive meow. When we moved she scampered off again.

A few nights later her behavior changed. She appeared at the witching hour again but she was restless. She kept pacing backwards and forwards over the bed and around the side. Every so often she came up to Helen's face and touched it gently with her nose and whiskers - Helen's eyes, nose and mouth. She kept being drawn back to our bed in the farthest, darkest corner of the apartment as if by a magnet.

Helen finally pushed her down to the bottom of the bed where she sat huddled up with wide eyes. Helen claims she felt the cat looking at her all night. Her dreams about the cat disturbed her sleep.

In the morning Cordy was still there, sitting on the end of the bed, its wide eyes looking at us, not comfortable and relaxed, yet not wanting to move.

Finally it was time to get up and we decided it was time Cordy went home too. We didn't mind her being there but she wasn't ours and the woman next door might be getting worried.

So Helen picked her up and took her down the steps from the landing, over to the fire balcony, and put her out the door. Cordy wasn't having any of it. Her ears went back, her eyes went wider still, and as soon as she was released she scampered back across the floor, shot up the steps to our mezzanine floor and plonked herself on our bed again. When I went up to her she looked at me defiantly and a little piteously too.

I said to Helen, "She must have had a fright on the balcony last night and is scared to go back across it. I'll shut the door on her so she'll have to discover that whatever scared her has gone."

I was quite wrong. As soon as she found she was trapped on the balcony, she leapt on our windowsill and crawled along it as far as she could go. She looked quite crazy and frantic, jerking her head around nervously at every noise.

It was far too worrying to see here there. She could fall – or jump - to the street in her wild state. I opened the door and called her back in.

I picked her up and cradled her in my arms. She accepted the gesture, her little heart beating furiously.

Nevertheless she had to go back to her owner. I took her out to the corridor. Her ears pricked up. Her head and eyes alertly scanned the hallway. I thought, she hasn't been out here before, she's wondering what's happening.

Her owner answered the door and let me in. Immediately the mystery was solved. A large young amiable Airedale dog loped up to us.

Cordy freaked. Her fur stood on end. She raced up my right arm and onto my shoulders. She took a panic-stricken leap at the stairs leading up to her owner's mezzanine landing. In her haste she misjudged her footing. She tumbled and rolled down half a dozen stairs before her claws dug in and stopped her. She flipped herself up and was out of sight in a flash.

My arm, neck and shoulders received a few scratches but nothing serious.

The woman told me Cordy would hide in the back of her darkest deepest closet. The dog had arrived the night before and the woman was looking after it for a month.

The other cat, Mary, had quickly worked out an arrangement where she ignored the dog and the dog kept its distance. Cordy hadn't acquired enough maturity and experience to be able to do the same. The dog was friendly but its size and smell overwhelmed poor Cordy.

I told the woman about the cat across the road, and that I hadn't seen it since. She said, "It won't be back. That was a nice cat too."

That's what I thought, but we were both wrong. The cat came back. I saw it yesterday, sitting on the window ledge sunning itself and licking its fur. It was thinner than I remembered it, and its black stripes seemed darker, more prominent. It gave me pleasure to see it. Except the old questions rose again in my mind. Where did it go? What did it do? And a new, more engrossing and immediate question: Will I see it go away again?

* * * * *

The cat across the road was more adventurous and accomplished than I first thought. He was capable of an amazing number of tricks. It was like living across the road from a one-cat circus.The cat lived on the third floor of a dirty grey five-storey building made of concrete. Like all the other buildings on that side of Warren Street it was a dingy narrow place well past its prime. Years of the city's dirt and soot clung to its façade.

It used to be an employment office. Now the top two floors were empty, the next two down were each occupied by an artist and a musician, and the ground floor was used to store the local street-vendors' handcarts overnight.

Four narrow windows were crammed along the frontage and the builders used these in a crude attempt to pretty up the place. The window ledges were made of pre-molded concrete and had two little footings at each end, like vertical bookends. The tops of the windows were even uglier. They were similar in design to the sills but thicker and heavier, and longer too. Whereas the window ledges had a foot-and-a-half gap between them, the overhangs on top nearly touched each other.

Both features had their uses. To the cat they were as broad as the roadway below. He trotted along them with assurance on his journeys up and down the face of the buildings. He was like a rock-climbing enthusiast. He had conquered all the vertical territory from the third floor windowsills up to the top floor, not only of his own building but of the narrow brick building to the left. He had also found a way to the roof of the three-storey apartment house on the right.

To me his journeys were as exciting and unexpected as trapeze artists and high-wire walkers in the circus. Except the cat had no ropes nor safety net.

The grimy windows on the third floor masked the room beyond. One of the windows was always open because of a dirty white flagpole poking out of it like a jaunty cigarette in the mouth of a gap-toothed bum. The open window revealed nothing. It was a black impenetrable hole. It's always from this window that the cat began its adventurous journeys.

The longest and most adventurous journey I saw the cat make began one morning when he leapt out of the blackness of his room onto the windowsill. He paused, as if taking a bow, then strolled along the windowsills towards the brick building on the left.

There is a three-foot gap between the windowsill and the wrought-iron fire escape on the brick building. There is also an iron railing around the fire balcony, with vertical guards about eight inches apart. To get from his building to the next, he had to jump a three-foot gap from the window ledge to the wrought-iron fire balcony on the brick building. He had to pass through the eight-inch gaps in the iron supports of the railing. And he had to land on a floor of flat, spaced-out iron bars. Not the best surface to land on even for a sure-footed cat.

It was like watching a circus lion jump through a hoop, except this hoop was 40 feet above the street. Yet it was all done with the nonchalance of someone travelling a difficult yet familiar road.

The cat picked his way sure-footedly over the iron bars of the fire balcony, then ran up the near-vertical iron ladder to the next landing above. It was done in two short sharp sprints. The steps were two close-set iron bars. The cat climbed by using his forepaws rather than his pads. When he paused, halfway up, his paws hung over the edge of the steps like the hands of a man leaning on his forearms on a railing.

This took the cat up the fire balcony on the fourth floor of the brick building next door. He cautiously went to one end of the balcony, just sniffing around. Then he returned to the ladder … and did the same trick again, up to the fifth floor.

This time he walked back towards his own place. When he reached the end of the fire balcony, he poked his head through the rails – and jumped.

His leap took him onto the highway of the thick ugly concrete overhangs that topped off the fourth floor windows of his own building. He prowled slowly along. The white droppings of pigeons could be seen dribbling over the edge.

When he came to the end of the second overhang he stopped. He looked up at the windowsills above, the windowsills of the fifth floor. He was about 60 feet up from the street, but he didn't look down. He seemed much more curious about how much further up he could go.

His mind was made up. At the same moment, not hurriedly but with grace and conviction, he gathered his limbs together and leapt upwards.

It was a breathtaking moment. Here he was clinging to a narrow ledge high above the concrete sidewalk below. Then, without any apparent thought and with utmost confidence, he made a lazy leap skywards to an even narrower ledge three or four feet higher.

It took a fraction of time. A flash of complete concentration and he had arrived. He disappeared through a broken pane in the fifth floor window.

The memory of that magical leap lingered on. It was a rare feat, and one that it looked like he'd never be able to repeat. But that's getting ahead of my story.

I now knew what was driving him on. I'd often seen him on the comparative safety of his own windowsill looking intently across and down. I'd follow his line of sight and he was always interested in a pigeon waddling around on the street below. He also watched them on the windowsills above him. He knew their favorite roosting places. He wanted to try out his hunting luck.

* * * * *

I'd watched the pigeons myself. On one occasion a very cheeky male pigeon flew onto a fifth-floor windowsill. A staid matronly pigeon was already there. The male bird strutted his stuff for a few moments, then moved in on the female. The courtship lasted a decent interval … about five minutes or so. He circled round her, then they started pecking at each other. It began like a fight but soon they were pecking at each other's beaks, like kisses. His wings would flap up, they would circle around again, and then start kissing once more.Suddenly there was a flurry of feathers. He rose in the air and dropped down onto her back. A few moments and it was all over.

The female started preening herself while he strutted to the end of the window ledge.

At this point I was about to return to my work when the male pigeon flew off the ledge onto the roof of the three-storey building to the right. He landed on the edge of the roof, then sidled back a little, out of sight of the windowsills.

Here I laughed out loud. Only minutes after his previous conquest, he started going through the same ritual with another female pigeon. But out of sight of the other, as if he didn't want to get a reputation as a fickle lover.

* * * * *

The gray and black cat wasn't through with showing me his extraordinary agility. His return journey opened up a whole new dimension.This time when I noticed him, he was on top of the windows on the third floor, his floor, but a level too high. It looked like he had just returned from the roof of the three-storey building on the right.

His movements were much more exploratory and tentative. He was heading downwards towards home this time. He could see how far he would fall if he missed his target.

He crept behind the long, disused vertical neon sign that ran down the full length of the building. It advertised an Employment Agency that once operated there.

It was a bulky sign, and it soon became apparent that it was hollow. For the cat finally made his decision and jumped down inside it.

This trick took him about a quarter way down the length of the windows. It was also probably a roosting place of the pigeons, particularly in bad weather. As they had led him up to the fifth floor, it seemed appropriate that they should show him the way back down as well.

The cat's head poked out from the back of the sign. He was still in trouble. Although he had found a safe ledge, he was still a good five feet up from the third-floor windowsills.

He cautiously inched his body out of the sign. His forepaws crept down the outside of his perch. His eyes looked anxiously down at the sill. So near, yet still a large – and dangerous – jump, to home.

He teetered out as far as he could without actually letting go. Then, gathering his resources, he sprang.

His tail stuck straight up from his backside. It acted as a balance and even perhaps as a partial air brake. The rigidity of the erect tail betrayed the tension of the jump.

He landed safely and immediately trotted along the windowsills to his own open window. His tail trailed languidly behind him.

He casually sprang out of sight and disappeared. The transformation from tense effort to casual insouciance was instantaneous. Once done he gave it no further thought.

1980