In 1919 D. H. Lawrence finally escaped from England, the country he had vowed never to live in again. He had been trapped there during a brief holiday in 1914 by the outbreak of World War I. For more than five years he fought desperately to leave the country but was refused the necessary travel documents. He suffered suspicion and prejudice because of his sexual beliefs, and because of his marriage to Frieda von Richtofen, cousin of the famous German fighter ace known as the Red Baron.

The British authorities finally allowed him to leave the country in November 1919. Lawrence never lived in Britain again but the pattern of prejudice and oppression was established. Ten years later many of his paintings were nearly destroyed by British authorities. The paintings were permanently banned from the country instead, and few people now know he ever painted.

On his world travels Lawrence discovered Taos, a dusty little town high in the desert mountains of northern New Mexico. He fell in love with it, bought a ranch and settled down for a while. It is in this remote spot that ten of his most controversial paintings are found today.

The most remarkable feature of Taos is a 14th century Indian pueblo, a collection of orange-brown adobe houses piled one on top of the other. It squats like a giant anthill on the outskirts of town. Over the centuries new rooms were grafted onto the sides and top. It is now five stories high and houses nearly 2,000 Indians.

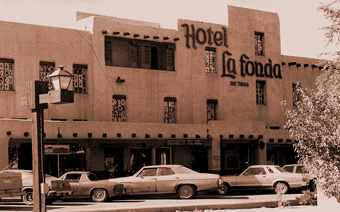

Taos has borrowed the same adobe style and mingled it with Spanish hacienda architecture and the log-cabin-and-boardwalk look of a pioneering town that grew out of the desert dust. The famous frontiersman Kit Carson spent most of his life here.

The high desert atmosphere and blending of cultures has produced a most strange and beautiful town. It has combined the primitive mystery of the original pueblo Indian, the color of Mexico, and the passion of Spain, with the wealth of the United States. The result is an eerily foreign town that belongs to no definite time or country but only to itself.

A framed antique sign hangs in the doorway of the Hotel la Fonda de Taos in the town square. It has hung there for more than 20 years. The sign proclaims the only exhibition of D. H. Lawrence's paintings since they were confiscated by Scotland Yard in 1929 and banned from Great Britain.

The hotel doorway opens into an L-shaped lobby with a huge log fire blazing in the corner. The walls and tables have been dressed by a colorful and eccentric hand. Beauty, violence and death are the dominating images.

Flamboyant canvases of boats piled high with thousands of many-colored flowers dazzle the eye. Bronze carvings of toreadors and bullfights line the walls. The carved wooden icon of a Spanish saint wearing a hat hangs on a crucifix behind a locked iron grill on the wall. A firing squad is lined up at its feet. Dusty plastic flower droop around it.

Lawrence's paintings are nowhere to be seen at first, but dotted amongst the bizarre decorations are framed newspaper clippings. They tell the story of his paintings.

D. H. Lawrence started painting at the age of 40. True to his character and reputation it became, as he said, "an orgy."

Before he died four years later he succeeded in outraging public opinion in Britain yet again by depicting his sexual beliefs in this unfamiliar medium. Paintings of his nudes created an enormous sensation at an exhibition in London in June 1929. In three weeks 13,000 people flocked through the Warren Galleries to see them.

The reaction of the critics was damning. The Daily Express critic wrote: "The ugly composition, coloring and drawing of these works are repellent enough, but the subjects of some of them will compel most spectators to recoil in horror."

The critic of the Daily Telegraph had a more personal slant: "To encounter a friend, particularly of the opposite sex, in the Warren Galleries, is, to say the least of it, highly embarrassing."

It was all too much for the official British sensibility. Complaints were laid, and on the murky evening of 5 July a squad of Scotland Yard detectives swooped. They carried off 13 paintings and a number of Lawrence's books. They also grabbed a volume of drawings by William Blake. That book was returned with some embarrassment when the detectives learned that Blake had been dead for a hundred years.

A week after the raid an 82-year-old magistrate ruled that Lawrence's paintings were obscene. But he did concede they need not be destroyed, provided they joined Lawrence in exile and never returned to endanger British morality again.

Following this story around the walls, picking through the confusion of art that fills the lobby area, one eventually stumbles on an office door in the most obscure corner of the hotel. A sign reads: "Exhibition of Lawrence Paintings, Admission $1."

Behind the sign is a tiny low-roofed office cluttered with filing cabinets, books, papers and a huge desk. A dozen or more pairs of black shoes line up along one wall. A small Indian boy appears silently to polish a pair then disappears again.

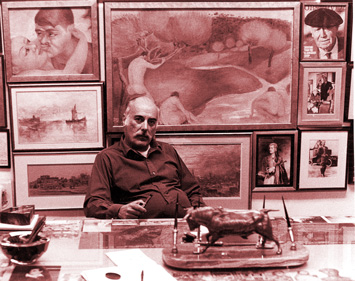

Lawrence's paintings are discovered at last, crammed on walls already packed with other paintings and framed photographs of celebrities and European nobility. Many of the photographs include Saki Karavas, owner of the hotel. Karavas acquired the paintings from the estate of Lawrence's wife Frieda after she died in 1956.

Although he was born in New York, Karavas is a Greek. He has the charm of an aristocrat and the eccentricity of a man who has always gone his own way. He sits quite comfortably in the bizarre splendor of his unusual hotel. He has a direct penetrating gaze. His sentences are so short they are often cryptic.

Karavas openly admits he bought the paintings as an investment. Frieda told him that one of the Rothschilds and the late Aga Khan wanted to buy them.

The paintings reek with sensuality. Breasts and buttocks abound. Lawrence's technique is not slick but it is expressive and often humorous. The images are tastefully stated, showing the raw power of sex without the obsessive explicitness or coyness of pornography. The implications and echoes linger in the mind.

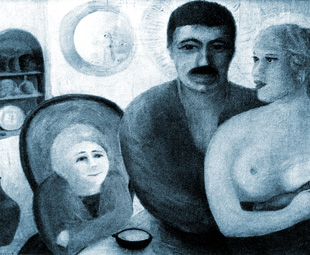

Lawrence himself admitted he couldn't draw but he said he could "make pictures." The first painting he did is called "A Holy Family." It shows the father with his arm affectionately around his bare-breasted wife while a small child looks on. It is an intriguing and subtle scene.

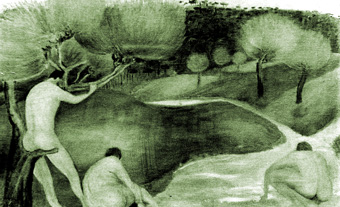

There are others. A naked satyr struggles with an Amazon surrounded by baying wolves. A naked man and woman dance beside a he-goat prancing on its hind legs. One of the largest is a lyrical study of three nudes quietly contemplative in an open meadow, while another painting is a blatant display of bare backs and buttocks called "The Rape of the Sabine Women."

In one of his verses written after the raid Lawrence described where he thought the real interest of British art-lovers lay:

13,000 people came to see

my pictures, eager as the honey bee

for the flowers; I'll tell you what,

all eyes sought the same old spot

in every picture, every time ...

and they stared and they stared, the halfwitted lot,

at the spot where the fig leaf was not.

It seems likely that the paintings will never be seen in Britain again. A British art organization wrote to Karavas about the 50th anniversary of Lawrence's death being commemorated in March 1980. It wanted to mark the occasion by exhibiting the paintings in Britain again for the first time in 50 years.

Karavas was wary. He could see the implications. He wrote to the British Home Secretary to find out whether the 1929 magisterial order still held.

The Home Secretary would make no assurances. He said the climate of opinion towards obscenity in Great Britain had undoubtedly changed, but he couldn't interfere with court decisions. Karavas didn't want to risk his investment so he turned the invitation down.

Karavas won't say how much the paintings cost him, but he told a Newsweek reporter several years ago that he'd sell them for $50,000. Since then they have mushroomed in value. A few months ago Karavas turned down an offer of $800,000 from President Portillo of Mexico.

Karavas firmly believes they are worth much more. He says he values them at $1.5 million.

He is not obsessed with money. His stand is part of his concept of what is right, what is fitting. For he says if he can't get the price he wants, he will give the paintings away to the people of Greece. It is a quixotic gesture aimed at correcting what he sees as wrong.

"I'll tell you why," he said. "Greece is a poor country. There are so many Greek treasures in English museums. I think it is only right that some English treasures go to Greece."

Then he did a most extraordinary thing. While he was talking Karavas smoked his pipe constantly, dropping the used matches into a tin wastepaper basket. Inevitably the paper in the bin caught fire. Karavas crushed the paper into the bottom of the bin to smother the flames, and went on talking.

The fire flared up again. Karavas looked down curiously. He seemed drawn by the flames. He lit a match and dropped it in to help them along. He lit another and then another.

The flames leapt out of the mouth of the bin. Karavas was satisfied. He returned to the conversation.

The cramped room filled with the suffocating fumes of burning paper. The small Indian boy flitted silently in and out through the smoke, polishing the shoes.

Karavas kept on talking. He showed not the slightest awareness that anything unusual was happening.

The fire died down and the smoke thinned out. The glass fronts of the million-dollar paintings glinted through the haze. Their future looked just as uncertain as ever.

Sunday Advocate, Baton Rouge, LA, 1980

The British authorities finally allowed him to leave the country in November 1919. Lawrence never lived in Britain again but the pattern of prejudice and oppression was established. Ten years later many of his paintings were nearly destroyed by British authorities. The paintings were permanently banned from the country instead, and few people now know he ever painted.

On his world travels Lawrence discovered Taos, a dusty little town high in the desert mountains of northern New Mexico. He fell in love with it, bought a ranch and settled down for a while. It is in this remote spot that ten of his most controversial paintings are found today.

The most remarkable feature of Taos is a 14th century Indian pueblo, a collection of orange-brown adobe houses piled one on top of the other. It squats like a giant anthill on the outskirts of town. Over the centuries new rooms were grafted onto the sides and top. It is now five stories high and houses nearly 2,000 Indians.

Taos has borrowed the same adobe style and mingled it with Spanish hacienda architecture and the log-cabin-and-boardwalk look of a pioneering town that grew out of the desert dust. The famous frontiersman Kit Carson spent most of his life here.

The high desert atmosphere and blending of cultures has produced a most strange and beautiful town. It has combined the primitive mystery of the original pueblo Indian, the color of Mexico, and the passion of Spain, with the wealth of the United States. The result is an eerily foreign town that belongs to no definite time or country but only to itself.

A framed antique sign hangs in the doorway of the Hotel la Fonda de Taos in the town square. It has hung there for more than 20 years. The sign proclaims the only exhibition of D. H. Lawrence's paintings since they were confiscated by Scotland Yard in 1929 and banned from Great Britain.

The hotel doorway opens into an L-shaped lobby with a huge log fire blazing in the corner. The walls and tables have been dressed by a colorful and eccentric hand. Beauty, violence and death are the dominating images.

Flamboyant canvases of boats piled high with thousands of many-colored flowers dazzle the eye. Bronze carvings of toreadors and bullfights line the walls. The carved wooden icon of a Spanish saint wearing a hat hangs on a crucifix behind a locked iron grill on the wall. A firing squad is lined up at its feet. Dusty plastic flower droop around it.

Lawrence's paintings are nowhere to be seen at first, but dotted amongst the bizarre decorations are framed newspaper clippings. They tell the story of his paintings.

D. H. Lawrence started painting at the age of 40. True to his character and reputation it became, as he said, "an orgy."

Before he died four years later he succeeded in outraging public opinion in Britain yet again by depicting his sexual beliefs in this unfamiliar medium. Paintings of his nudes created an enormous sensation at an exhibition in London in June 1929. In three weeks 13,000 people flocked through the Warren Galleries to see them.

The reaction of the critics was damning. The Daily Express critic wrote: "The ugly composition, coloring and drawing of these works are repellent enough, but the subjects of some of them will compel most spectators to recoil in horror."

The critic of the Daily Telegraph had a more personal slant: "To encounter a friend, particularly of the opposite sex, in the Warren Galleries, is, to say the least of it, highly embarrassing."

It was all too much for the official British sensibility. Complaints were laid, and on the murky evening of 5 July a squad of Scotland Yard detectives swooped. They carried off 13 paintings and a number of Lawrence's books. They also grabbed a volume of drawings by William Blake. That book was returned with some embarrassment when the detectives learned that Blake had been dead for a hundred years.

A week after the raid an 82-year-old magistrate ruled that Lawrence's paintings were obscene. But he did concede they need not be destroyed, provided they joined Lawrence in exile and never returned to endanger British morality again.

Following this story around the walls, picking through the confusion of art that fills the lobby area, one eventually stumbles on an office door in the most obscure corner of the hotel. A sign reads: "Exhibition of Lawrence Paintings, Admission $1."

Behind the sign is a tiny low-roofed office cluttered with filing cabinets, books, papers and a huge desk. A dozen or more pairs of black shoes line up along one wall. A small Indian boy appears silently to polish a pair then disappears again.

Lawrence's paintings are discovered at last, crammed on walls already packed with other paintings and framed photographs of celebrities and European nobility. Many of the photographs include Saki Karavas, owner of the hotel. Karavas acquired the paintings from the estate of Lawrence's wife Frieda after she died in 1956.

Although he was born in New York, Karavas is a Greek. He has the charm of an aristocrat and the eccentricity of a man who has always gone his own way. He sits quite comfortably in the bizarre splendor of his unusual hotel. He has a direct penetrating gaze. His sentences are so short they are often cryptic.

Karavas openly admits he bought the paintings as an investment. Frieda told him that one of the Rothschilds and the late Aga Khan wanted to buy them.

The paintings reek with sensuality. Breasts and buttocks abound. Lawrence's technique is not slick but it is expressive and often humorous. The images are tastefully stated, showing the raw power of sex without the obsessive explicitness or coyness of pornography. The implications and echoes linger in the mind.

Lawrence himself admitted he couldn't draw but he said he could "make pictures." The first painting he did is called "A Holy Family." It shows the father with his arm affectionately around his bare-breasted wife while a small child looks on. It is an intriguing and subtle scene.

There are others. A naked satyr struggles with an Amazon surrounded by baying wolves. A naked man and woman dance beside a he-goat prancing on its hind legs. One of the largest is a lyrical study of three nudes quietly contemplative in an open meadow, while another painting is a blatant display of bare backs and buttocks called "The Rape of the Sabine Women."

In one of his verses written after the raid Lawrence described where he thought the real interest of British art-lovers lay:

13,000 people came to see

my pictures, eager as the honey bee

for the flowers; I'll tell you what,

all eyes sought the same old spot

in every picture, every time ...

and they stared and they stared, the halfwitted lot,

at the spot where the fig leaf was not.

It seems likely that the paintings will never be seen in Britain again. A British art organization wrote to Karavas about the 50th anniversary of Lawrence's death being commemorated in March 1980. It wanted to mark the occasion by exhibiting the paintings in Britain again for the first time in 50 years.

Karavas was wary. He could see the implications. He wrote to the British Home Secretary to find out whether the 1929 magisterial order still held.

The Home Secretary would make no assurances. He said the climate of opinion towards obscenity in Great Britain had undoubtedly changed, but he couldn't interfere with court decisions. Karavas didn't want to risk his investment so he turned the invitation down.

Karavas won't say how much the paintings cost him, but he told a Newsweek reporter several years ago that he'd sell them for $50,000. Since then they have mushroomed in value. A few months ago Karavas turned down an offer of $800,000 from President Portillo of Mexico.

Karavas firmly believes they are worth much more. He says he values them at $1.5 million.

He is not obsessed with money. His stand is part of his concept of what is right, what is fitting. For he says if he can't get the price he wants, he will give the paintings away to the people of Greece. It is a quixotic gesture aimed at correcting what he sees as wrong.

"I'll tell you why," he said. "Greece is a poor country. There are so many Greek treasures in English museums. I think it is only right that some English treasures go to Greece."

Then he did a most extraordinary thing. While he was talking Karavas smoked his pipe constantly, dropping the used matches into a tin wastepaper basket. Inevitably the paper in the bin caught fire. Karavas crushed the paper into the bottom of the bin to smother the flames, and went on talking.

The fire flared up again. Karavas looked down curiously. He seemed drawn by the flames. He lit a match and dropped it in to help them along. He lit another and then another.

The flames leapt out of the mouth of the bin. Karavas was satisfied. He returned to the conversation.

The cramped room filled with the suffocating fumes of burning paper. The small Indian boy flitted silently in and out through the smoke, polishing the shoes.

Karavas kept on talking. He showed not the slightest awareness that anything unusual was happening.

The fire died down and the smoke thinned out. The glass fronts of the million-dollar paintings glinted through the haze. Their future looked just as uncertain as ever.

Sunday Advocate, Baton Rouge, LA, 1980