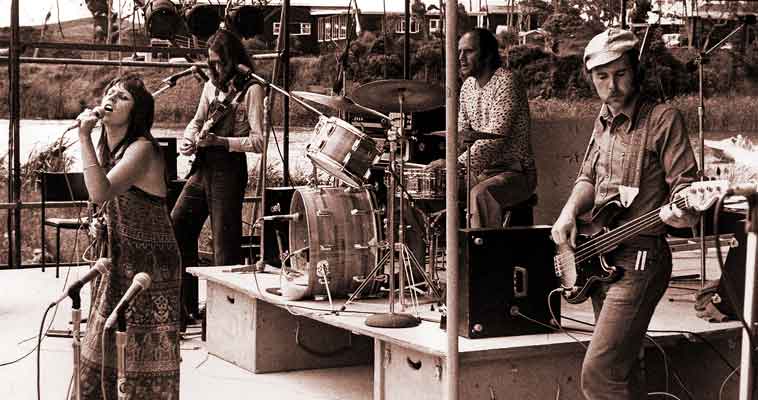

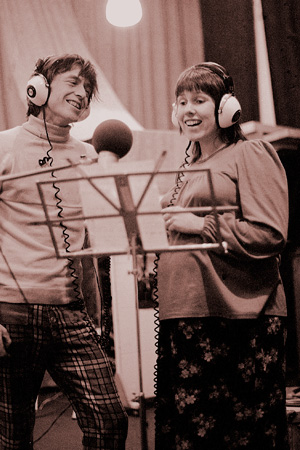

Geoff Murphy and Beaver recording the song

"Bank Man"

Beaver is furious.

"Look, they've done it again," she hisses. She can hardly believe it. Every time, the same ... insult, almost.

Beaver has arrived to sing at one of her favourite venues, the Gluepot in Auckland's Ponsonby Road, just up the road from where she lives. This is her territory. She's a celebrity here.

Beaver likes the Gluepot and the Gluepot likes her. But every time - every time - the same thing happens. Her name appears nowhere. Her appearance has not been announced. She is launching once more into a dark void.

"I have lots of friends round here," she says. "How are they to know I'm singing if they don't put a sign out?"

She walks in. The advertising blackboard is propped up against the wall just inside the door. It still advertises the group that played the weekend before.

The worst is yet to come. Like all bad news, it is not long in arriving.

The Gluepot has in fact advertised her performance in the evening paper. A respectable two-inch ad even. But when Beaver sees the paper, there is her name in bold caps: BEABER.

They can't even get that right.

Deep down, she finds excuses for them. After all, she still gets paid. They are the ones who miss out by not advertising properly. And they can hardly be blamed for the paper's misprint. Besides, she likes it here.

Beaver sighs and asks her manager, Paul Walker, to take it up with the Gluepot. It is not her style to make a scene. She prefers to make people feel good. So she gets on with the job of delivering another night of good songs and swinging music.

That's how she operates. She feels strongly, but doesn't always express it when the feeling is negative. There is only one time when she will open up and let you know, richly, seductively, exactly how she feels - when she sings.

On Blerta she was always introduced as "The Lovely Beaver." That's how everyone thought of her. She was so sweet and open, she was easy to take advantage of.

These days her friends will assure you that Beaver will not be pushed around any more. There is some truth in that. In the past she may not even have noticed her name was not up front, or if she did, she would not have presumed to mention it. Now there is more iron in her soul.

For instance, when she first arrived in Auckland, she scored a long stint singing at the Foundry in Nelson Street. Four nights a week, 10 till 2 or 3 in the morning, flat tack. The place was always full. It was hard work, but she loved it. That was when she discovered, after a couple of years, that all the other musicians were paid more than she was.

It came out, as these things always do, by accident. They got a pay rise. Beaver, who was a solo parent with two daughters, was ecstatic. She crowed with delight. "Isn't it great? Fancy getting 180 bucks a week," she said. "Yahoo!"

The others shuffled and coughed behind their hands. They were getting $200. The news left Beaver dry mouthed and speechless.

There was an explanation, of course. Among other things, the singer before Beaver used to start an hour later. But Beaver still thinks the band was as much to blame as the management because they did nothing about it. It didn't matter to them that she went to all the rehearsals and started the same time they did, "Coughing up with the goods," she says. It was part of the male musicians' general attitude towards women. The Heavies, she calls them. If she tried to make a point about anything, they used to get a bit ruffled. A bit sort of, well who are you, what are you talking about, bloody woman hassling away. She had some uncomfortable moments.

When it came to the point, she had to fight her own battle with the management. She went by herself to ask for her extra 20 dollars. "I was very teary-eyed upset. I was hardly banging on the table and demanding anything. I was just so upset. They said, Yes, definitely, we'll raise it to the same as the boys."

Beaver can chuckle about it now. "I said, And I want back pay! And they said, Ooh, you'll be lucky."

"We had this silly thing where Bruce Cutfield was called Broody Bum, Lance was called Lacy Bum and Margaret Ward was called Tortoise," she says. "All silly names that just evolved. My name's Beverly. It's terribly derivative, isn't it? It just kind of stuck, even for professional things." Nobody has ever been so unkind as to suggest that with her charmingly prominent front teeth, she looks, well, slightly beaverish.

Beaver graduated from Wellington Technical College in art. On the way she won a scholarship for music and took up the clarinet. Her musical bent was encouraged by her father, who is a classical pianist and an artist.

"We have yahoos at home," Beaver says. "We sing all the shows and everything. He has all the music. We go through the show songs and yell and scream and rant and rave and his brother and the wives all sing. It's good fun. Any family occasion is always a hoot-up that way. It's old-fashioned stuff but I know it all. I grew up with it."

She sang in her father's choirs and even won a singing competition one year. "I don't know how," she says. "I just remember this period of extreme panic." But she did not think of herself as a singer. So when she got a music scholarship, she decided to take up an instrument. She thought she would like to learn the double bass, but it was too hard. Her fingers couldn't hold down those big fat strings.

She thought, what else do I like - I like the saxophone.

Her family said, "No. no. The saxophone is not an orchestral instrument."

She said, "OK, French horn?"

And they said, "Bloody difficult."

She said, "Oboe?"

They said, "Yeah, oboe, you're getting close."

Then they all kept saying, "Why don't you do the clarinet?"

So she reluctantly took up the clarinet. Her mother wanted Beaver to learn violin, but she couldn't imagine that happening. She got quite good at the clarinet but she doesn't play it any more.

Beaver became a designer for UEB packaging for two or three years. Then during the late 1960s she got bitten by the hippy bug. She started bumming around in bare feet and loose dresses and meeting all these interesting people.

Cameraman Alun Bollinger was her boyfriend at the time. One night Bollinger was with a bunch of people including Bruno Lawrence. Bollinger said he had to pick up his girlfriend. They all drove round and Beaver hopped in the car. Bruno immediately pegged her as a singer.

Bollinger said, "This is Beaver."

Beaver said hullo and Bruno heard her voice. The voice spoke to him. It seemed to have a real magic quality about it. He started asking questions just to listen to the voice. He finally had to ask. He said, "God, what a voice - do you sing?"

Beaver blushed furiously and shrugged, and said, "No."

Bollinger said, "Yes, she does. She won a cup at school and a scholarship."

In those days Bruno hung out a lot at the Wellington Musicians' Club. Somehow or other he wangled her up there one night. Then he said, "C'mon, have a sing." This wasn't just a sing-song and Beaver knew it. But she got up anyway and was really good. Bruno could tell. She had natural timing and a feel for a song.

Beaver was still a teenager when she was sniffing around the Musicians' Club. She loved the scene, the variety, the strangeness of it all. But she was still very shy. She did not like to get up there and be noticed.

"Bruno would drag young musicians along by the scruff of their necks and chuck them on the stage," she says. "He'd start crashing away on the drums and whoever it was would just have to play along and all the people there would have to suffer the whole bit. I guess he'd always do that with me. He'd say, Sing, damn you, get on with it."

She also listened to a lot of music. Her friends bought the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. She bought jazz records, John Berry movie themes and singers like Barbara Streisand and Sarah Vaughan.

"I used to hide in my bedroom with my own little record player and play all these singers," she says. "I suppose I sang with them but I wasn't conscious of wanting to be a singer. But then, I'm a late developer, aren't I? I wasn't conscious of a helluva lot in those days. I was just in a dream world."

Blerta was her first real performance in public. "It was terrifying," Beaver says.

Bruno hit on the idea of a summer tour in a bus, taking the wives and kids along. There would be music, actors, and films. They wouldn't just be concerts, they would be shows, extravaganzas, a riot of fantasy, good music and anarchy. At the same time, they would roam the country and have a good time.

Bruno roped in Geoff Murphy to play trumpet, make films, and stage the special effects. Bruno wanted lots of explosions.

The idea just grew and grew. A whole bunch of musicians and helpers flocked to the bus. Corben Simpson was in his first flowering and became the main singer, but Bruno wanted Beaver as well. He had to work hard to track her down though. He heard she was in Christchurch, so he rang there. No, he was told, she's back in Wellington. He rang Beaver's mother. No, Mrs Morrison said, she's back in Christchurch. Those were the days when Beaver used to hitchhike round a lot and have what she calls "a neato free time."

Finally Bruno put it to her. "This time we've really got something," he said. "This time it's going to work."

Beaver was absolutely terrified. But that was no answer. She couldn't say, nope, I'm frightened. She had to say, all right, I'll do it. So she did.

Beaver hid her terror so well that Bruno didn't even notice. All he could see was his dream coming true.

Audiences loved her voice. Bruno watched her blossom. She used to get up in her nightie, that was her costume. Blerta was rag-tag anyway in those days, in hand-me-down costumes. People made up their own stage gear, their own props.

Corben was very confident and that helped. Beaver found she could slip into harmonics naturally with other people without any sweat. So they managed to arrange a few production numbers by the end of the first tour. Beaver fitted in perfectly and that, of course, chuffed Corben.

Even in those early days, when Beaver opened her mouth on stage to sing, people would stop talking and heads would turn. It was just like in the Hollywood movies. You could see it. Not as corny as the movies, they wouldn't gather round and burst into tumultuous applause at the end of the song. But her voice would cut through to them, it would capture their attention and keep it focussed on her.

Filmmaker and entrepreneur Graham Mclean felt it too the first time he saw her. She was performing with Blerta in the Queenstown school hall, in the New Year of 1972. McLean's brother was there as well, and his girlfriend. They all reacted the same way. Often you hear a song and it's just a voice in the background and you get on dancing. But when Beaver started singing, Mclean and his friends stopped. They didn't just listen but they watched her. She has that kind of magnetism.

Beaver fell for him. Who wouldn't?

It was all a bit scandalous for a while, but finally they got it together. Stalker fathered Beaver's two lovely daughters, Frith and Kate.

When Blerta finished that first tour, Stalker set out to become a pro actor. Naturally, he took Beaver with him. He encouraged her to become more professional. Whereas Blerta got her rolling and encouraged her artistically, he encouraged her showbiz-wise. Stalker gave her confidence. He helped to stoke the fires.

Unfortunately, he was mostly trying to get her to develop an acting career. It seemed to Beaver that he was always a bit funny and jealous about her singing life. He didn't like her doing all the things that she liked to do most. He always shoved her in the direction that he wanted to go. It drove her crazy. Beaver became a nervous wreck.

Stalker controlled all the money. She was earning money as well, but he organised it. "He did all the shopping too," Beaver says, "because I didn't do it well enough. It's true!"

When she demanded some money to buy some shoes for herself, he'd come home with shoes for her. The trouble was, she didn't like them. "So when I started kicking up a fuss about doing what I wanted to do and having my own cheque book and everything, the shit hit the fan," Beaver says. "It was all a bit crazy. I'm not blaming Bill for all of it. Obviously I put up with it for a goodly while, blindly put up with it, thinking this is how it was, this is how it is, not realising that I was eating away, wasting away."

But, of course, the other thing was that he was a fabulous guy. Beaver still loves him. That's why their separation, and later, his death, was so painful for her. "We became really, really good mates after we separated," she says. "It took a while, but we did. I'm still very close to him." She slips into present tense occasionally, even though he died in a motorbike accident in 1982.

Stalker helped Beaver to get a part in the television soap opera Close to Home. That was after both the kids were born. She played a singer called Sammy James who was Alex Fleming's girl friend. Stalker was Alex Fleming. The job was his idea, to keep earning money. You earn better money as an actor than you do as a singer. Beaver was both, but she didn't like the idea too much. The acting took too much away from her singing. Besides, with typical modesty, she felt she was sticking her neck out a bit calling herself an actor. She felt it wasn't really fair to those actors who had been slogging away for years.

But mainly, she didn't have the time or the energy for singing any more. She worked six days a week on Close to Home. And she had two small kids to look after as well. "I was working flat out and drinking too much," Beaver says. "Oh, it was a hard, hard life."

It was too much in the end. What really finished them as a couple was that Stalker was too strong. He got his own way too often.

"I just couldn't stand always doing what he wanted to do," she says. "I had to start sticking up for myself and start doing what I wanted to do. I couldn't be my own person and live with him at the time. I wanted to be a singer and a mother."

They scored a two-week season in Auckland. The experience convinced them that Auckland was where they wanted to be. So they all packed up and moved to Auckland, the band, Red Mole and Beaver.

After that group split up, she got heavily into Auckland's night club scene. The first job was at Clio's in Mt Wellington. Then she moved to the Foundry in Nelson Street.

At first she couldn't believe it. The noise level was horrendous. There were half-hour breaks while the disco took over. She wasn't used to that. She thought, what am I going to do in these huge long breaks? I'll write letters. I'll read books.

Of course she did nothing of the sort. They all made for the band room. It was a broom cupboard they all squashed into. They had a hilarious time. It became one of the social spots of Auckland. People came to visit them there. Other musicians started turning up because the band was really hot.

Overseas musicians came there too. The Rod Stewart band came. Chicago turned up a few times and had a blow. Beaver had a wonderful time.

Beaver met a physio student called Al. They started going out together and a few months later decided to get married. "I had a few savings so we blew them," she says. "Had a party. Bought a new outfit."

Life was looking good. It often does before disaster strikes.

One day Beaver took one of the kids to the doctor. He looked at Beaver and said, "Have you got a sore throat?"

Beaver said, "No."

"Well, have you got a cold?"

She said, "No."

He didn't let it go. He said, "What's wrong with your voice then?"

Beaver said, "Nothing. I'm a singer, I always talk like this."

By this time she was singing at Gillies. She was husky from the late nights in smokey, drinkey atmospheres, singing hard over inadequate PA systems, competing with noisy musicians and electronic gear that the human voice can't possibly hope to beat. She had a mike but she could hardly hear herself sing. She was convinced that half the people in the club couldn't hear her either.

The doctor packed her off to see an ear, nose and throat specialist. He confirmed it. Throat nodules it was.

The specialist said, "It's over to you, but I advise you to have them taken off. We do each side separately."

Beaver said, "I can't really afford to be off work." She was thinking of the two kids and Al was a full-time student by then.

"You'll only need to take 10 days off after each side," the specialist said.

So Beaver told the band she'd take a week off to clear up the nodules. She had the first side done and found she couldn't talk, let alone sing. When the time came to go back to work, she couldn't. She was worried sick. She still thought of her fellow musicians as a bunch of heavies.

A month later she had the other side done, and it was even worse. She had to go on Accident Compensation. It delighted the pants off the surgeons. They thought that was the funniest thing they'd ever heard of, a woman pop singer getting compo.

It wasn't funny for Beaver. It was dreadful. The break was OK at first because it had been a hard life for her. But when it turned into an 18-month layoff, it didn't do her head any good at all. She felt guilty. She thought it was her fault she got the nodules in the first place. It shattered her confidence.

And of course life just went on without her. None of the musicians seemed to care. Hardly anybody rang up or called round to see if she was all right. The whole world just marched on. It was a bad time for her.

She was cut off from everything. And she didn't have the nerve to keep on going around and visiting people. She felt she couldn't be going in and out of night clubs anyway, because she was newly married. It didn't seem right.

Lindsay Dobbie knew Beaver was looking for work. At that time Lindsay was helping to run a vegetable business that supplied restaurants and ran a retail trade in front. They sold herbs, nuts, fruit and vegetables. Beaver joined her and did mornings with Lindsay for three months until neither of them could stand the work any more. Beaver kept getting things wrong and giving the wrong change. She thought she was hopeless. But Lindsay thought she was fine, and they became firm friends.

Beaver's luck started to change for the better again. There was greater grief to come, but her climb back into the world began.

Philcox even taught Beaver how to sing again, although she wasn't really a singing teacher. She told Beaver she was a little worried about the singing part of her voice, but she figured it would all follow through if she got Beaver talking properly, using her voice correctly, breathing properly, and understanding voice production in general.

Beaver went for it. She said, "Yeah, let's do it." They started working together at Philcox's house with her piano.

Lindsay was astounded. She thought Beaver was a fabulous singer. She couldn't see the need for Beaver to have singing lessons. Particularly from someone who wasn't even a proper singing teacher. But Lindsay started to realise that it was also a confidence thing. When Beaver first began singing again in front of an audience she was throttling her words. She was afraid to let go. The lessons taught her what she needed to know about her voice.

It was not only the lessons. Beaver was helped a lot by her women friends in the neighbourhood. The two went hand in hand. She had more time to get to know other women around her. Until she moved to Herne Bay, she never really felt as though she had any good mates. She worked mostly with men, always at night.

One friend Beaver made in the business, Angela Griffen, thought that Beaver's new friends were essential to her development. Griffen organised the entertainment for Club Mirage in 1980. Beaver became one of her favourite entertainers.

Griffen realised that Beaver felt tremendously dependent on her musician friends. But suddenly she had time to meet other women outside her work. She had a wider input of opinions and tastes to react to.

"I think that women are far more into the nitty gritty," Griffen says. "What makes you tick, what you like and don't like. Where you stand - if you're a singer, why you sing, who you sing with, do you like them, if you don't like them, why don't you.

"Also she had time to dwell on things. After years of bringing up children, trying to earn a living, making ends meet, all those sorts of things which are really important when you've got two girls, she had time to think. It's probably the first time for 10 years that she had time to talk to other women."

Beaver loves her new community. She enjoys their sympathy. She borrows their clothes. They go to the beach and have lunches together. Most of all, she is just one of them. "They never stick me on a pedestal or treat me like a weirdo," she says.

She could feel her voice getting better and better. Then she was offered a job at a cafe on Ponsonby Road. Just her and a pianist, Peter Wood. "A wonderful piano player and a really good chum," she says. She took the plunge.

She didn't feel good about it for a while. "I used to sweat buckets every night. It was terrible. I also didn't feel that I had any clothes or presentation any more."

Nevertheless, things were coming right. She was getting it happening again. Her fortune was looking up.

Then Bill Stalker was killed on his motorbike in Melbourne.

Lindsay says, "She probably didn't grieve enough in the beginning. She hid a fair bit of it, for Alistair's sake, I suppose. About four or five months afterwards she became very depressed again. It's something that she had to work through. I guess it's difficult when you're in one relationship and another has finally ended."

Al found it difficult too. He couldn't understand how Beaver could be so down for so long. Beaver had to get away for a while.

"I just couldn't get into grieving," Beaver says. "I had to keep a stiff upper lip and I kept collapsing everywhere. I thought, I better go and see my mother. My mother was great. She let me do what I wanted to do and I got better much more quickly."

All this bad experience had a good side. Beaver came out of it fighting fit. She's been through the worst of it. Now she could move on.

Angela Griffen thought the change was dramatic. "Suddenly she realised it didn't matter who she sang with, she was still Beaver and she could do most things and do them well. She took on quite a number of new assignments, jobs with different people. But she also began to insist, in certain circumstances where she thought it was important to her, on getting the best. She wanted the best pianist and the best bassist, instead of just putting up with whatever came along."

She can do anything from just voice and piano, through the jazz thing, to fronting a rock and roll band. "She can sing better than anyone else in the country," rocker Hammond Gamble says. Top jazz bassist Andy Brown says, "She's really easy to play with." Long-time pianist Crombie Murdoch says, "She's one of the best about." Bruno Lawrence sums it up: "Beaver's always such a delight to work with. I love playing drums with Beav because it's quite magic. It seems effortless, it's really good fun."

Part of her comeback was the creation of the All Stars. An old friend, Paul Walker, and Beaver decided to get the best rock musicians together for a bit of a jam at the Windsor Castle in Parnell. They called it, "The All Stars Play the Blues." The first one had Beaver, Billy Christian, Sonny Day, Ricky Ball and Willy Dayson. The place was packed out two nights in a row. It was a lot of work to organise, so they don't do it every week. But every so often it happens again, with a different line-up of musicians.

As an experiment Paul Walker put Beaver with pianist Terry Crayford for a hotel bar tour. He called it, "Beaver Sings Bar Room Ballads." They played Nelson and Golden Bay. It was a great success.

Walker discovered that wherever she was, Beaver attracted a following of all ages, of all kinds of people. He also found that most people had already heard of her and remembered her. "That's amazing when you think she's never had a record out and her television appearances of any regularity were at least five years ago," he says.

Beaver hasn't recorded because she isn't a hustler. She knows the limits of her talents and is happy with them. "I'm a singer and a mother," is her refrain. If other people want to organise a record and include her, that's all right by her.

"Anywhere else in the world Beaver would have been snapped up by somebody," Bruno Lawrence says. "Like a manager or a producer or something. She should have done four or five albums by now. But New Zealand lacks enough people with that kind of energy."

Now a manager has snapped her up. Her friend Paul Walker. Beaver thinks that's swell. "It makes life a lot easier," she says. "He does all the boring bits."

He not only manages her, he recently married her as well.

Beaver sings the theme songs for two feature films released in 1985, and stars in one of them. The biggest hit was Ian Mune's Came a Hot Friday. When it came to getting a singer, Mune thought Beaver was the natural choice.

"We thought of doing all the things that the movie industry is always thinking of, like let's get Linda Rondstadt," Mune says. "But when it came to the crunch, we thought, let's use a Kiwi, we're using Kiwis for everything else. Let's use the one with the most grunt. It had to be Beaver."

Friday's theme song, "This Time," needed a lot of power and a lot of control. "It's a helluva difficult song," Mune says. "You've really got to have the lungs to handle it. It's very fast. It's full of lyrics, the words come piling in. You have to get into a very strong beat. Then you need all of your lungs for the end as well."

The other film was Graham Mclean's Should I Be Good. You could call it a television film on sex, drugs and rock and roll. Many reviewers agreed that the best thing in it was Beaver.

Mclean says, "She's not a trained actress, but she's got so much emotion and experience to draw on that you can bring it out of her. She's just amazing."

To Mclean, there is no question about it, Beaver is a star. He says, "On stage or anywhere else it's a matter of someone having to project their personality or the part out to an audience. But in a film it's totally different. You can get in there, you can get in close. Beaver doesn't even have to speak, she just has to react and she's got an amazing reservoir of emotion. It comes across in every movement. She's got this amazing face which just speaks."

The band swings into an old standard that Beaver loves and does so well. It's called "Them There Eyes." The music pops along. Beaver loses herself in the lyrics. Her eyes flash and sparkle until you think the song must have been written for her.

When Beaver started, the room was practically empty. Not many people knew she was appearing tonight. Now it is full. All the tables are taken and the bar is lined with people. Their backs are to the bar. They are captured by Beaver. She is her own best advertisement.

That's Beaver. A singer and a mother. Her singing rarely makes you brush a tear away. She just makes you feel good.

More Magazine, New Zealand, 1986

"Look, they've done it again," she hisses. She can hardly believe it. Every time, the same ... insult, almost.

Beaver has arrived to sing at one of her favourite venues, the Gluepot in Auckland's Ponsonby Road, just up the road from where she lives. This is her territory. She's a celebrity here.

Beaver likes the Gluepot and the Gluepot likes her. But every time - every time - the same thing happens. Her name appears nowhere. Her appearance has not been announced. She is launching once more into a dark void.

"I have lots of friends round here," she says. "How are they to know I'm singing if they don't put a sign out?"

She walks in. The advertising blackboard is propped up against the wall just inside the door. It still advertises the group that played the weekend before.

The worst is yet to come. Like all bad news, it is not long in arriving.

The Gluepot has in fact advertised her performance in the evening paper. A respectable two-inch ad even. But when Beaver sees the paper, there is her name in bold caps: BEABER.

They can't even get that right.

Deep down, she finds excuses for them. After all, she still gets paid. They are the ones who miss out by not advertising properly. And they can hardly be blamed for the paper's misprint. Besides, she likes it here.

Beaver sighs and asks her manager, Paul Walker, to take it up with the Gluepot. It is not her style to make a scene. She prefers to make people feel good. So she gets on with the job of delivering another night of good songs and swinging music.

That's how she operates. She feels strongly, but doesn't always express it when the feeling is negative. There is only one time when she will open up and let you know, richly, seductively, exactly how she feels - when she sings.

On Blerta she was always introduced as "The Lovely Beaver." That's how everyone thought of her. She was so sweet and open, she was easy to take advantage of.

These days her friends will assure you that Beaver will not be pushed around any more. There is some truth in that. In the past she may not even have noticed her name was not up front, or if she did, she would not have presumed to mention it. Now there is more iron in her soul.

For instance, when she first arrived in Auckland, she scored a long stint singing at the Foundry in Nelson Street. Four nights a week, 10 till 2 or 3 in the morning, flat tack. The place was always full. It was hard work, but she loved it. That was when she discovered, after a couple of years, that all the other musicians were paid more than she was.

It came out, as these things always do, by accident. They got a pay rise. Beaver, who was a solo parent with two daughters, was ecstatic. She crowed with delight. "Isn't it great? Fancy getting 180 bucks a week," she said. "Yahoo!"

The others shuffled and coughed behind their hands. They were getting $200. The news left Beaver dry mouthed and speechless.

There was an explanation, of course. Among other things, the singer before Beaver used to start an hour later. But Beaver still thinks the band was as much to blame as the management because they did nothing about it. It didn't matter to them that she went to all the rehearsals and started the same time they did, "Coughing up with the goods," she says. It was part of the male musicians' general attitude towards women. The Heavies, she calls them. If she tried to make a point about anything, they used to get a bit ruffled. A bit sort of, well who are you, what are you talking about, bloody woman hassling away. She had some uncomfortable moments.

When it came to the point, she had to fight her own battle with the management. She went by herself to ask for her extra 20 dollars. "I was very teary-eyed upset. I was hardly banging on the table and demanding anything. I was just so upset. They said, Yes, definitely, we'll raise it to the same as the boys."

Beaver can chuckle about it now. "I said, And I want back pay! And they said, Ooh, you'll be lucky."

* * * * *

Beaver was born in Wellington in 1950. Her real name is Beverly Jean Morrison. She got her nickname at primary school. All the kids in her class had one."We had this silly thing where Bruce Cutfield was called Broody Bum, Lance was called Lacy Bum and Margaret Ward was called Tortoise," she says. "All silly names that just evolved. My name's Beverly. It's terribly derivative, isn't it? It just kind of stuck, even for professional things." Nobody has ever been so unkind as to suggest that with her charmingly prominent front teeth, she looks, well, slightly beaverish.

Beaver graduated from Wellington Technical College in art. On the way she won a scholarship for music and took up the clarinet. Her musical bent was encouraged by her father, who is a classical pianist and an artist.

"We have yahoos at home," Beaver says. "We sing all the shows and everything. He has all the music. We go through the show songs and yell and scream and rant and rave and his brother and the wives all sing. It's good fun. Any family occasion is always a hoot-up that way. It's old-fashioned stuff but I know it all. I grew up with it."

She sang in her father's choirs and even won a singing competition one year. "I don't know how," she says. "I just remember this period of extreme panic." But she did not think of herself as a singer. So when she got a music scholarship, she decided to take up an instrument. She thought she would like to learn the double bass, but it was too hard. Her fingers couldn't hold down those big fat strings.

She thought, what else do I like - I like the saxophone.

Her family said, "No. no. The saxophone is not an orchestral instrument."

She said, "OK, French horn?"

And they said, "Bloody difficult."

She said, "Oboe?"

They said, "Yeah, oboe, you're getting close."

Then they all kept saying, "Why don't you do the clarinet?"

So she reluctantly took up the clarinet. Her mother wanted Beaver to learn violin, but she couldn't imagine that happening. She got quite good at the clarinet but she doesn't play it any more.

Beaver became a designer for UEB packaging for two or three years. Then during the late 1960s she got bitten by the hippy bug. She started bumming around in bare feet and loose dresses and meeting all these interesting people.

Cameraman Alun Bollinger was her boyfriend at the time. One night Bollinger was with a bunch of people including Bruno Lawrence. Bollinger said he had to pick up his girlfriend. They all drove round and Beaver hopped in the car. Bruno immediately pegged her as a singer.

Bollinger said, "This is Beaver."

Beaver said hullo and Bruno heard her voice. The voice spoke to him. It seemed to have a real magic quality about it. He started asking questions just to listen to the voice. He finally had to ask. He said, "God, what a voice - do you sing?"

Beaver blushed furiously and shrugged, and said, "No."

Bollinger said, "Yes, she does. She won a cup at school and a scholarship."

In those days Bruno hung out a lot at the Wellington Musicians' Club. Somehow or other he wangled her up there one night. Then he said, "C'mon, have a sing." This wasn't just a sing-song and Beaver knew it. But she got up anyway and was really good. Bruno could tell. She had natural timing and a feel for a song.

Beaver was still a teenager when she was sniffing around the Musicians' Club. She loved the scene, the variety, the strangeness of it all. But she was still very shy. She did not like to get up there and be noticed.

"Bruno would drag young musicians along by the scruff of their necks and chuck them on the stage," she says. "He'd start crashing away on the drums and whoever it was would just have to play along and all the people there would have to suffer the whole bit. I guess he'd always do that with me. He'd say, Sing, damn you, get on with it."

* * * * *

Bruno always kept Beaver in mind and tried to get a few gigs going with her. For one reason or another none of them flew, partly because Beaver was too shy. She had no faith in her own potential. Once Bruno lined her up for a band on a cruise boat, but that fell through, too. In the meantime, Beaver hung out at the Musicians' Club, often with Eric Foley, who still figures largely in her life. They have performed every Sunday for the last four years to the lunchtime crowds at Carthew's restaurant on Ponsonby Road.She also listened to a lot of music. Her friends bought the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. She bought jazz records, John Berry movie themes and singers like Barbara Streisand and Sarah Vaughan.

"I used to hide in my bedroom with my own little record player and play all these singers," she says. "I suppose I sang with them but I wasn't conscious of wanting to be a singer. But then, I'm a late developer, aren't I? I wasn't conscious of a helluva lot in those days. I was just in a dream world."

Blerta was her first real performance in public. "It was terrifying," Beaver says.

Bruno hit on the idea of a summer tour in a bus, taking the wives and kids along. There would be music, actors, and films. They wouldn't just be concerts, they would be shows, extravaganzas, a riot of fantasy, good music and anarchy. At the same time, they would roam the country and have a good time.

Bruno roped in Geoff Murphy to play trumpet, make films, and stage the special effects. Bruno wanted lots of explosions.

The idea just grew and grew. A whole bunch of musicians and helpers flocked to the bus. Corben Simpson was in his first flowering and became the main singer, but Bruno wanted Beaver as well. He had to work hard to track her down though. He heard she was in Christchurch, so he rang there. No, he was told, she's back in Wellington. He rang Beaver's mother. No, Mrs Morrison said, she's back in Christchurch. Those were the days when Beaver used to hitchhike round a lot and have what she calls "a neato free time."

Finally Bruno put it to her. "This time we've really got something," he said. "This time it's going to work."

Beaver was absolutely terrified. But that was no answer. She couldn't say, nope, I'm frightened. She had to say, all right, I'll do it. So she did.

Beaver hid her terror so well that Bruno didn't even notice. All he could see was his dream coming true.

Audiences loved her voice. Bruno watched her blossom. She used to get up in her nightie, that was her costume. Blerta was rag-tag anyway in those days, in hand-me-down costumes. People made up their own stage gear, their own props.

Corben was very confident and that helped. Beaver found she could slip into harmonics naturally with other people without any sweat. So they managed to arrange a few production numbers by the end of the first tour. Beaver fitted in perfectly and that, of course, chuffed Corben.

Even in those early days, when Beaver opened her mouth on stage to sing, people would stop talking and heads would turn. It was just like in the Hollywood movies. You could see it. Not as corny as the movies, they wouldn't gather round and burst into tumultuous applause at the end of the song. But her voice would cut through to them, it would capture their attention and keep it focussed on her.

Filmmaker and entrepreneur Graham Mclean felt it too the first time he saw her. She was performing with Blerta in the Queenstown school hall, in the New Year of 1972. McLean's brother was there as well, and his girlfriend. They all reacted the same way. Often you hear a song and it's just a voice in the background and you get on dancing. But when Beaver started singing, Mclean and his friends stopped. They didn't just listen but they watched her. She has that kind of magnetism.

* * * * *

Bill Stalker was one of the actors on that tour. Stalker tells the young prince's story in the middle of the 1972 Blerta hit song, "Dance Around the World". The word "hunk" sits unashamedly on Stalker.Beaver fell for him. Who wouldn't?

It was all a bit scandalous for a while, but finally they got it together. Stalker fathered Beaver's two lovely daughters, Frith and Kate.

When Blerta finished that first tour, Stalker set out to become a pro actor. Naturally, he took Beaver with him. He encouraged her to become more professional. Whereas Blerta got her rolling and encouraged her artistically, he encouraged her showbiz-wise. Stalker gave her confidence. He helped to stoke the fires.

Unfortunately, he was mostly trying to get her to develop an acting career. It seemed to Beaver that he was always a bit funny and jealous about her singing life. He didn't like her doing all the things that she liked to do most. He always shoved her in the direction that he wanted to go. It drove her crazy. Beaver became a nervous wreck.

Stalker controlled all the money. She was earning money as well, but he organised it. "He did all the shopping too," Beaver says, "because I didn't do it well enough. It's true!"

When she demanded some money to buy some shoes for herself, he'd come home with shoes for her. The trouble was, she didn't like them. "So when I started kicking up a fuss about doing what I wanted to do and having my own cheque book and everything, the shit hit the fan," Beaver says. "It was all a bit crazy. I'm not blaming Bill for all of it. Obviously I put up with it for a goodly while, blindly put up with it, thinking this is how it was, this is how it is, not realising that I was eating away, wasting away."

But, of course, the other thing was that he was a fabulous guy. Beaver still loves him. That's why their separation, and later, his death, was so painful for her. "We became really, really good mates after we separated," she says. "It took a while, but we did. I'm still very close to him." She slips into present tense occasionally, even though he died in a motorbike accident in 1982.

Stalker helped Beaver to get a part in the television soap opera Close to Home. That was after both the kids were born. She played a singer called Sammy James who was Alex Fleming's girl friend. Stalker was Alex Fleming. The job was his idea, to keep earning money. You earn better money as an actor than you do as a singer. Beaver was both, but she didn't like the idea too much. The acting took too much away from her singing. Besides, with typical modesty, she felt she was sticking her neck out a bit calling herself an actor. She felt it wasn't really fair to those actors who had been slogging away for years.

But mainly, she didn't have the time or the energy for singing any more. She worked six days a week on Close to Home. And she had two small kids to look after as well. "I was working flat out and drinking too much," Beaver says. "Oh, it was a hard, hard life."

It was too much in the end. What really finished them as a couple was that Stalker was too strong. He got his own way too often.

"I just couldn't stand always doing what he wanted to do," she says. "I had to start sticking up for myself and start doing what I wanted to do. I couldn't be my own person and live with him at the time. I wanted to be a singer and a mother."

* * * * *

They broke up in 1978. Beaver took the kids to Auckland and started working there in clubs and bands. By that time she had been the feature singer on two Blerta LPs and in the television series Blerta, which won the Feltex Award in 1976. She got more television work singing on Pop Co and other shows. After acting in Close to Home she sang with Midge Marsden and the Country Fliers in the Red Mole shows at Carmen's Balcony in Wellington. It included a bit of fun cabaret-type acting. She called it "louting around on stage."They scored a two-week season in Auckland. The experience convinced them that Auckland was where they wanted to be. So they all packed up and moved to Auckland, the band, Red Mole and Beaver.

After that group split up, she got heavily into Auckland's night club scene. The first job was at Clio's in Mt Wellington. Then she moved to the Foundry in Nelson Street.

At first she couldn't believe it. The noise level was horrendous. There were half-hour breaks while the disco took over. She wasn't used to that. She thought, what am I going to do in these huge long breaks? I'll write letters. I'll read books.

Of course she did nothing of the sort. They all made for the band room. It was a broom cupboard they all squashed into. They had a hilarious time. It became one of the social spots of Auckland. People came to visit them there. Other musicians started turning up because the band was really hot.

Overseas musicians came there too. The Rod Stewart band came. Chicago turned up a few times and had a blow. Beaver had a wonderful time.

Beaver met a physio student called Al. They started going out together and a few months later decided to get married. "I had a few savings so we blew them," she says. "Had a party. Bought a new outfit."

Life was looking good. It often does before disaster strikes.

* * * * *

Beaver also started to build strong friendships with women for the first time in her life. Al had a job painting the house of Lindsay Dobbie, the manager of Raffles restaurant. Al liked what she'd done with the house, and asked if his wife could come and see it. Lindsay was immediately struck with Beaver because she arrived laden with flowers for the new house. Lindsay thought, what a gem. The friendship that started then was a great help when the trouble came.One day Beaver took one of the kids to the doctor. He looked at Beaver and said, "Have you got a sore throat?"

Beaver said, "No."

"Well, have you got a cold?"

She said, "No."

He didn't let it go. He said, "What's wrong with your voice then?"

Beaver said, "Nothing. I'm a singer, I always talk like this."

By this time she was singing at Gillies. She was husky from the late nights in smokey, drinkey atmospheres, singing hard over inadequate PA systems, competing with noisy musicians and electronic gear that the human voice can't possibly hope to beat. She had a mike but she could hardly hear herself sing. She was convinced that half the people in the club couldn't hear her either.

The doctor packed her off to see an ear, nose and throat specialist. He confirmed it. Throat nodules it was.

The specialist said, "It's over to you, but I advise you to have them taken off. We do each side separately."

Beaver said, "I can't really afford to be off work." She was thinking of the two kids and Al was a full-time student by then.

"You'll only need to take 10 days off after each side," the specialist said.

So Beaver told the band she'd take a week off to clear up the nodules. She had the first side done and found she couldn't talk, let alone sing. When the time came to go back to work, she couldn't. She was worried sick. She still thought of her fellow musicians as a bunch of heavies.

A month later she had the other side done, and it was even worse. She had to go on Accident Compensation. It delighted the pants off the surgeons. They thought that was the funniest thing they'd ever heard of, a woman pop singer getting compo.

It wasn't funny for Beaver. It was dreadful. The break was OK at first because it had been a hard life for her. But when it turned into an 18-month layoff, it didn't do her head any good at all. She felt guilty. She thought it was her fault she got the nodules in the first place. It shattered her confidence.

And of course life just went on without her. None of the musicians seemed to care. Hardly anybody rang up or called round to see if she was all right. The whole world just marched on. It was a bad time for her.

She was cut off from everything. And she didn't have the nerve to keep on going around and visiting people. She felt she couldn't be going in and out of night clubs anyway, because she was newly married. It didn't seem right.

Lindsay Dobbie knew Beaver was looking for work. At that time Lindsay was helping to run a vegetable business that supplied restaurants and ran a retail trade in front. They sold herbs, nuts, fruit and vegetables. Beaver joined her and did mornings with Lindsay for three months until neither of them could stand the work any more. Beaver kept getting things wrong and giving the wrong change. She thought she was hopeless. But Lindsay thought she was fine, and they became firm friends.

Beaver's luck started to change for the better again. There was greater grief to come, but her climb back into the world began.

* * * * *

The hospital board put her onto a marvellous woman who was a speech therapist at Greenlane Hospital. Her name was Nell Philcox. Beaver thought she was splendid and very thorough. Philcox dealt to Beaver's head, to her confidence, as well as to her voice.Philcox even taught Beaver how to sing again, although she wasn't really a singing teacher. She told Beaver she was a little worried about the singing part of her voice, but she figured it would all follow through if she got Beaver talking properly, using her voice correctly, breathing properly, and understanding voice production in general.

Beaver went for it. She said, "Yeah, let's do it." They started working together at Philcox's house with her piano.

Lindsay was astounded. She thought Beaver was a fabulous singer. She couldn't see the need for Beaver to have singing lessons. Particularly from someone who wasn't even a proper singing teacher. But Lindsay started to realise that it was also a confidence thing. When Beaver first began singing again in front of an audience she was throttling her words. She was afraid to let go. The lessons taught her what she needed to know about her voice.

It was not only the lessons. Beaver was helped a lot by her women friends in the neighbourhood. The two went hand in hand. She had more time to get to know other women around her. Until she moved to Herne Bay, she never really felt as though she had any good mates. She worked mostly with men, always at night.

One friend Beaver made in the business, Angela Griffen, thought that Beaver's new friends were essential to her development. Griffen organised the entertainment for Club Mirage in 1980. Beaver became one of her favourite entertainers.

Griffen realised that Beaver felt tremendously dependent on her musician friends. But suddenly she had time to meet other women outside her work. She had a wider input of opinions and tastes to react to.

"I think that women are far more into the nitty gritty," Griffen says. "What makes you tick, what you like and don't like. Where you stand - if you're a singer, why you sing, who you sing with, do you like them, if you don't like them, why don't you.

"Also she had time to dwell on things. After years of bringing up children, trying to earn a living, making ends meet, all those sorts of things which are really important when you've got two girls, she had time to think. It's probably the first time for 10 years that she had time to talk to other women."

Beaver loves her new community. She enjoys their sympathy. She borrows their clothes. They go to the beach and have lunches together. Most of all, she is just one of them. "They never stick me on a pedestal or treat me like a weirdo," she says.

She could feel her voice getting better and better. Then she was offered a job at a cafe on Ponsonby Road. Just her and a pianist, Peter Wood. "A wonderful piano player and a really good chum," she says. She took the plunge.

She didn't feel good about it for a while. "I used to sweat buckets every night. It was terrible. I also didn't feel that I had any clothes or presentation any more."

Nevertheless, things were coming right. She was getting it happening again. Her fortune was looking up.

Then Bill Stalker was killed on his motorbike in Melbourne.

* * * * *

Beaver had just had an ectopic pregnancy. She nearly died. She got home from hospital and the next day Stalker was killed. The combination was too much. It knocked her for a six. For the next year she was practically a write-off. It took so long partly because she wouldn't express her feelings at first.Lindsay says, "She probably didn't grieve enough in the beginning. She hid a fair bit of it, for Alistair's sake, I suppose. About four or five months afterwards she became very depressed again. It's something that she had to work through. I guess it's difficult when you're in one relationship and another has finally ended."

Al found it difficult too. He couldn't understand how Beaver could be so down for so long. Beaver had to get away for a while.

"I just couldn't get into grieving," Beaver says. "I had to keep a stiff upper lip and I kept collapsing everywhere. I thought, I better go and see my mother. My mother was great. She let me do what I wanted to do and I got better much more quickly."

All this bad experience had a good side. Beaver came out of it fighting fit. She's been through the worst of it. Now she could move on.

Angela Griffen thought the change was dramatic. "Suddenly she realised it didn't matter who she sang with, she was still Beaver and she could do most things and do them well. She took on quite a number of new assignments, jobs with different people. But she also began to insist, in certain circumstances where she thought it was important to her, on getting the best. She wanted the best pianist and the best bassist, instead of just putting up with whatever came along."

* * * * *

In the business, they call it paying your dues. All the grief, the disappointments, the struggles, the mistakes, the late nights. The good times and the bad. It was all coming together for Beaver. It was starting to pay off.She can do anything from just voice and piano, through the jazz thing, to fronting a rock and roll band. "She can sing better than anyone else in the country," rocker Hammond Gamble says. Top jazz bassist Andy Brown says, "She's really easy to play with." Long-time pianist Crombie Murdoch says, "She's one of the best about." Bruno Lawrence sums it up: "Beaver's always such a delight to work with. I love playing drums with Beav because it's quite magic. It seems effortless, it's really good fun."

Part of her comeback was the creation of the All Stars. An old friend, Paul Walker, and Beaver decided to get the best rock musicians together for a bit of a jam at the Windsor Castle in Parnell. They called it, "The All Stars Play the Blues." The first one had Beaver, Billy Christian, Sonny Day, Ricky Ball and Willy Dayson. The place was packed out two nights in a row. It was a lot of work to organise, so they don't do it every week. But every so often it happens again, with a different line-up of musicians.

As an experiment Paul Walker put Beaver with pianist Terry Crayford for a hotel bar tour. He called it, "Beaver Sings Bar Room Ballads." They played Nelson and Golden Bay. It was a great success.

Walker discovered that wherever she was, Beaver attracted a following of all ages, of all kinds of people. He also found that most people had already heard of her and remembered her. "That's amazing when you think she's never had a record out and her television appearances of any regularity were at least five years ago," he says.

Beaver hasn't recorded because she isn't a hustler. She knows the limits of her talents and is happy with them. "I'm a singer and a mother," is her refrain. If other people want to organise a record and include her, that's all right by her.

"Anywhere else in the world Beaver would have been snapped up by somebody," Bruno Lawrence says. "Like a manager or a producer or something. She should have done four or five albums by now. But New Zealand lacks enough people with that kind of energy."

Now a manager has snapped her up. Her friend Paul Walker. Beaver thinks that's swell. "It makes life a lot easier," she says. "He does all the boring bits."

He not only manages her, he recently married her as well.

Beaver sings the theme songs for two feature films released in 1985, and stars in one of them. The biggest hit was Ian Mune's Came a Hot Friday. When it came to getting a singer, Mune thought Beaver was the natural choice.

"We thought of doing all the things that the movie industry is always thinking of, like let's get Linda Rondstadt," Mune says. "But when it came to the crunch, we thought, let's use a Kiwi, we're using Kiwis for everything else. Let's use the one with the most grunt. It had to be Beaver."

Friday's theme song, "This Time," needed a lot of power and a lot of control. "It's a helluva difficult song," Mune says. "You've really got to have the lungs to handle it. It's very fast. It's full of lyrics, the words come piling in. You have to get into a very strong beat. Then you need all of your lungs for the end as well."

The other film was Graham Mclean's Should I Be Good. You could call it a television film on sex, drugs and rock and roll. Many reviewers agreed that the best thing in it was Beaver.

Mclean says, "She's not a trained actress, but she's got so much emotion and experience to draw on that you can bring it out of her. She's just amazing."

To Mclean, there is no question about it, Beaver is a star. He says, "On stage or anywhere else it's a matter of someone having to project their personality or the part out to an audience. But in a film it's totally different. You can get in there, you can get in close. Beaver doesn't even have to speak, she just has to react and she's got an amazing reservoir of emotion. It comes across in every movement. She's got this amazing face which just speaks."

* * * * *

Beaver's quartet is belting it out at the Gluepot in Ponsonby. The pianist Peter Wood grabs a pair of drumsticks. He goes wild for several choruses, trading four-bar breaks on the tom-toms with the drummer, Frank Conway. It is stirring stuff. Bits of Wood's drumstick fly in the air. By the end, it is smashed to splinters.The band swings into an old standard that Beaver loves and does so well. It's called "Them There Eyes." The music pops along. Beaver loses herself in the lyrics. Her eyes flash and sparkle until you think the song must have been written for her.

When Beaver started, the room was practically empty. Not many people knew she was appearing tonight. Now it is full. All the tables are taken and the bar is lined with people. Their backs are to the bar. They are captured by Beaver. She is her own best advertisement.

That's Beaver. A singer and a mother. Her singing rarely makes you brush a tear away. She just makes you feel good.

More Magazine, New Zealand, 1986